Beyond Earth's Limits: The Compelling Advantages of Space-Based Manufacturing for Advanced Materials

Executive Summary

The industrial landscape is on the cusp of a monumental shift, moving beyond the terrestrial sphere and into the vast expanse of space. This transition is driven not by exploratory curiosity, but by industrial necessity. As Earth-bound manufacturing processes increasingly encounter fundamental physical and economic limitations, the unique environment of space—characterized by microgravity, ultra-high vacuum, and a distinct radiation profile—offers a compelling alternative for producing a new generation of advanced materials. This report details the profound advantages of in-space manufacturing, with a particular focus on the production of highly ordered crystalline structures for the semiconductor, pharmaceutical, and fiber optic industries. By examining the underlying physics and reviewing the progress of pioneering commercial ventures, this report will demonstrate that space is poised to become a critical extension of our global industrial supply chain, enabling the creation of products with unprecedented purity, performance, and value.

1. Introduction

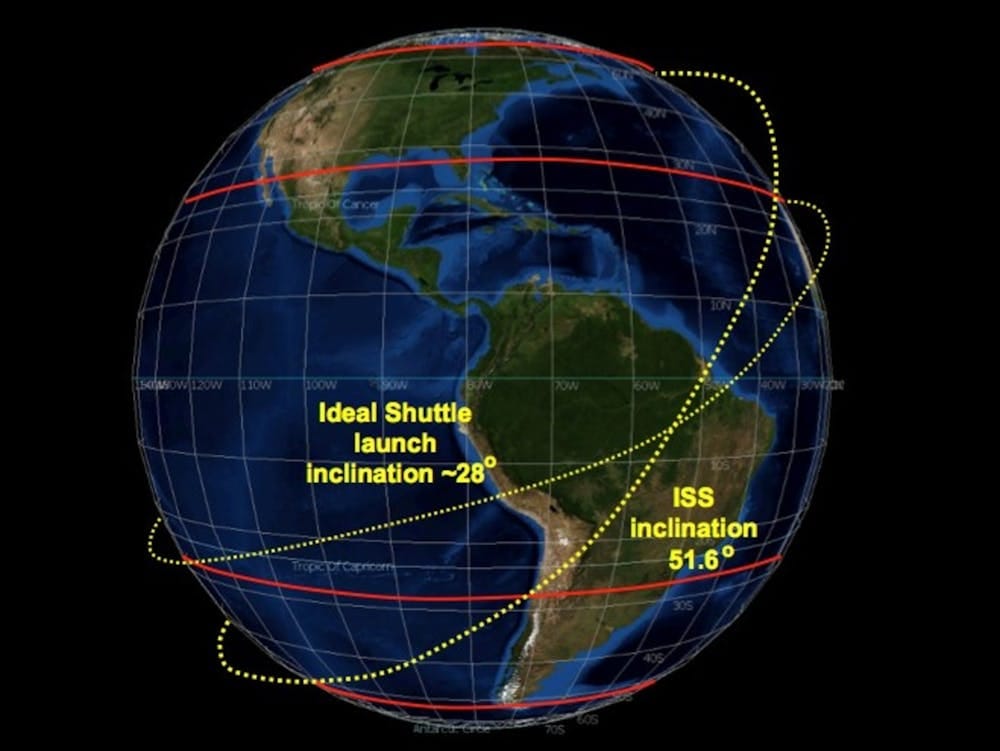

For decades, manufacturing has been a terrestrial endeavor, bound by the laws of physics as we experience them on Earth's surface. Gravity, atmospheric pressure, and a filtered radiation environment have dictated the means of production, the quality of materials, and the ultimate limits of innovation. However, the relentless drive for technological advancement, from more powerful microchips to more effective medicines, is now straining these terrestrial boundaries. Industries are facing escalating costs associated with creating the pristine, controlled environments required for high-performance materials, such as the multi-billion dollar cleanrooms for semiconductor fabrication [1].

In response to these challenges, a new frontier is opening: the industrialization of space. The convergence of reusable launch vehicles, which are drastically reducing the cost of accessing orbit, and the urgent demand for superior materials is transforming Low Earth Orbit (LEO) into a viable manufacturing hub. This report explores why it is increasingly more interesting and advantageous to build in space versus on Earth, focusing on the production of crystalline materials. We will delve into the specific benefits for semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and advanced optical fibers, highlighting how the absence of gravity-induced defects and contamination can lead to products that are physically impossible to create on our home planet.

Figure 1: The International Space Station (ISS) serves as a critical platform for microgravity research and the development of in-space manufacturing technologies. (Image credit: NASA)

2. The Fundamental Physics: Why Space is Different

The business case for space manufacturing is rooted in the unique physical properties of the orbital environment. These are not incremental improvements over terrestrial conditions; they are fundamentally different, enabling entirely new processes and material characteristics.

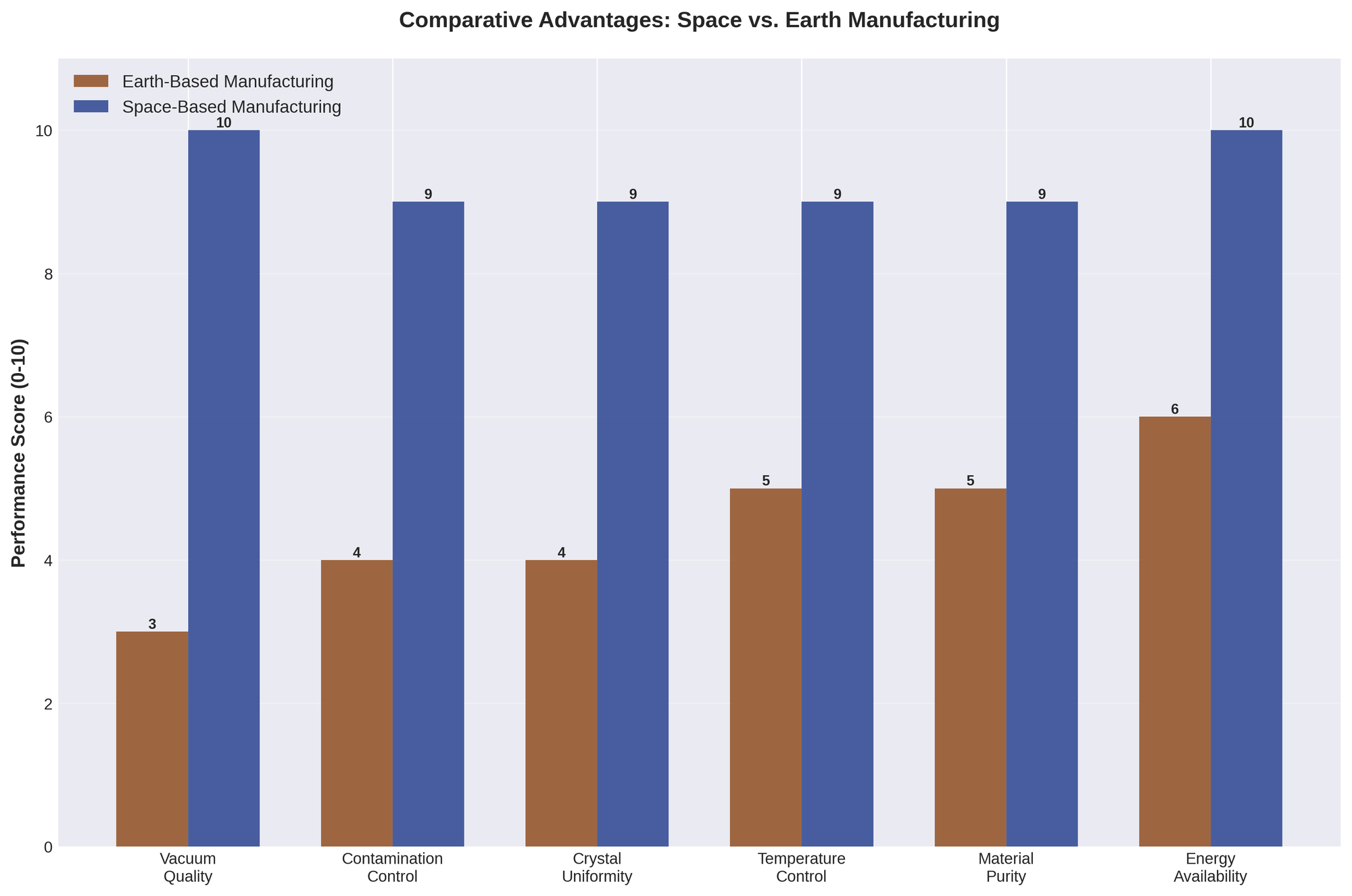

Figure 2: A comparison of key manufacturing factors, highlighting the significant performance advantages of the space environment over terrestrial methods across multiple domains.

2.1 Microgravity Environment

The near-weightlessness of space, or microgravity, is perhaps the most significant advantage. Its effects are profound, primarily through the elimination of two gravity-driven phenomena: convection and sedimentation.

On Earth, when a fluid (liquid or gas) is heated, its density changes, causing it to move. This process, known as buoyancy-driven convection, creates currents and turbulence that are highly disruptive to delicate processes like crystal growth [2]. In microgravity, these currents are virtually nonexistent. Fluid transport is instead dominated by the much slower and more orderly process of diffusion, allowing atoms and molecules to arrange themselves into more perfect crystal lattice structures without being jostled by turbulent flows. This results in crystals that are larger, more uniform, and have far fewer defects than their terrestrial counterparts [3].

Furthermore, microgravity eliminates sedimentation, the tendency for denser materials to settle out of a mixture. This allows for the creation of perfectly homogenous alloys and composite materials that would separate on Earth. It also enables containerless processing, where a material can be melted, solidified, or processed while levitating, untouched by any surface. This prevents the introduction of impurities from a container wall, a significant source of contamination in high-purity material production on Earth [4].

2.2 Ultra-High Vacuum

On Earth, creating a vacuum requires expensive, energy-intensive chambers and powerful pumps. Even then, achieving an "ultra-high vacuum" (UHV) is a significant engineering challenge. In contrast, the environment of space is a natural and near-perfect vacuum, readily available and vast. For processes like semiconductor fabrication, where even a single stray particle can ruin a microchip, this is a game-changing advantage.

The cost of creating and maintaining the pristine, particle-free cleanrooms required for modern chip foundries is astronomical; a new facility from a manufacturer like TSMC can cost upwards of $50 billion, with a significant portion of that expense dedicated to environmental control and contamination prevention [5]. By moving certain fabrication steps into the natural vacuum of space, companies can bypass these immense terrestrial costs and achieve a level of purity that is difficult to replicate on the ground. This is the core strategy for companies like Besxar, which aims to leverage the vacuum of space to produce ultra-pure semiconductor substrates [6].

2.3 Radiation Environment

While often viewed as a hazard to be shielded against, the unique radiation environment of space also presents opportunities for research and development. The constant bombardment by cosmic rays and solar particles, unfiltered by an atmosphere, can be used to accelerate aging studies for materials and biological systems. This allows researchers to observe the long-term effects of degradation in a compressed timeframe. For the beauty and personal care industry, this offers a way to test the efficacy of anti-aging products under harsh conditions [7]. For pharmaceutical research, it provides insights into disease progression and can reveal new information about how cells respond to stress, potentially uncovering new therapeutic targets [7].

3. Semiconductor Manufacturing in Space

The semiconductor industry is the bedrock of the digital economy, yet it faces immense challenges in its quest for smaller, faster, and more efficient chips. The manufacturing process is exquisitely sensitive to defects, and as components shrink to the atomic scale, the limitations of terrestrial fabrication become increasingly apparent. Space offers a radical solution to many of these problems.

3.1 The Terrestrial Challenge

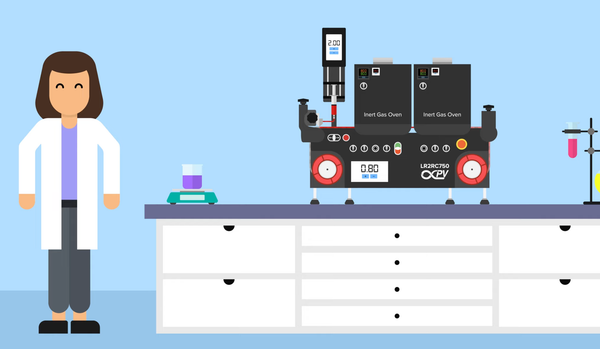

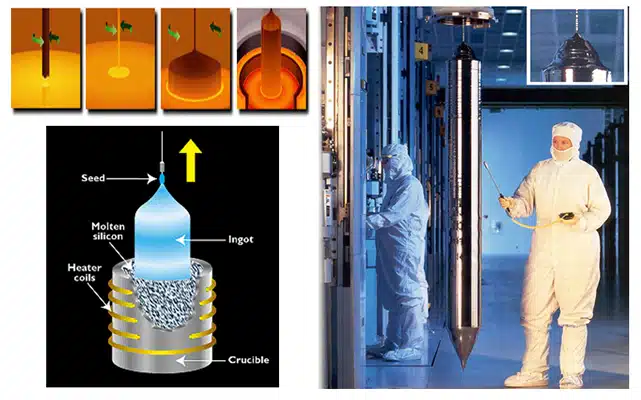

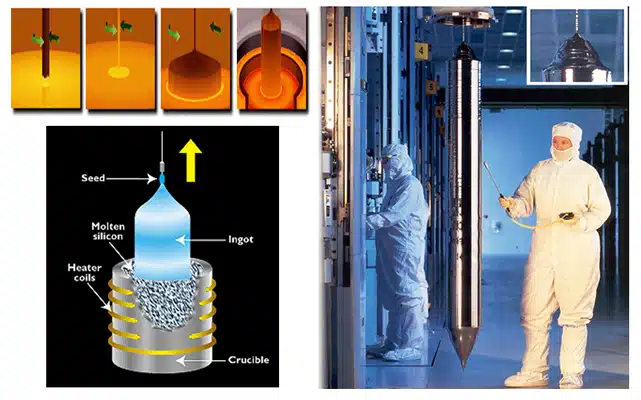

Modern semiconductor foundries are among the most complex and expensive manufacturing facilities on Earth. The primary challenge is maintaining an environment of near-perfect cleanliness. A single speck of dust can render a multi-million dollar batch of wafers useless. This necessitates the construction of massive, highly-sanitized cleanrooms where air is filtered to an extreme degree. Furthermore, the process of growing large, single-crystal silicon ingots—the raw material for wafers—is susceptible to gravity-induced defects, which reduce the overall yield of usable chips [8]. The physical stresses and convection currents present during crystal growth on Earth can introduce dislocations and impurities that impair electronic performance.

Figure 3: The Czochralski method is a common technique for producing single-crystal silicon ingots on Earth. The process is sensitive to gravity-induced convection and impurities. (Image credit: WaferPro)

3.2 Space-Based Solutions

Pioneering companies are now developing novel approaches to move critical semiconductor manufacturing processes off-planet. Their strategies leverage the unique advantages of the space environment to create superior materials.

Besxar Space Industries is taking a unique approach by focusing on the ultra-high vacuum of space rather than microgravity alone. The company has contracted with SpaceX to fly "Fabship" payloads on Falcon 9 boosters. These automated pods will perform high-purity fabrication processes during the 10-minute suborbital flight and return to Earth with the booster, allowing for rapid iteration and analysis [6]. Their goal is to produce ultra-pure semiconductor substrates, viewing orbit as a critical extension of the domestic semiconductor supply chain.

Space Forge, a UK-based startup, is focused on growing next-generation semiconductor crystals like silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) in orbit. These materials are crucial for high-power electronics in electric vehicles and 5G networks. By growing these crystals in microgravity, Space Forge aims to produce wafers with far fewer defects, which would drastically reduce the energy wasted as heat in electronic devices [2]. Their ForgeStar satellite platform is designed as a reusable, orbital factory that can return the finished crystals to Earth.

3.3 Technical Advantages and Impact

The benefits of producing semiconductors in space are multifaceted. The absence of gravity-induced convection and sedimentation allows for the growth of crystals with a near-perfect lattice structure, free from the defects and stress cracks that plague terrestrial production [2]. The natural vacuum eliminates sources of contamination, potentially increasing yields and enabling the creation of novel thin-layer materials that are impossible to make in the presence of atmospheric gases [1].

The impact of these improvements could be transformative. For applications like electric vehicles, more efficient power electronics made from space-grown SiC could significantly reduce the size and weight of the cooling systems, which can account for up to 20% of an electric air taxi's mass [2]. This weight reduction could translate directly to increased range or passenger capacity, fundamentally altering the economics of electric transportation. For the AI industry, higher-purity chips mean faster processing with less energy consumption, addressing a key bottleneck in the scaling of large AI models.

4. Pharmaceutical Crystallization in Space

Perhaps one of the most mature and economically compelling areas of in-space manufacturing is in the pharmaceutical sector. The development of new drugs is a long, expensive, and arduous process, often hinging on a detailed understanding of the three-dimensional structure of proteins. Obtaining this understanding is a major bottleneck, and it is one that microgravity is uniquely suited to solve.

4.1 The Science of Protein Crystallization

Many diseases are caused by malfunctioning proteins. To design effective drugs, scientists must understand the precise shape of these proteins to create molecules that can interact with them. The gold standard for determining a protein's structure is a technique called X-ray crystallography. This method requires the protein to first be grown into a solid, highly ordered crystal. When a beam of X-rays is aimed at the crystal, the rays diffract in a pattern that can be computationally reconstructed into a 3D model of the protein molecule [3].

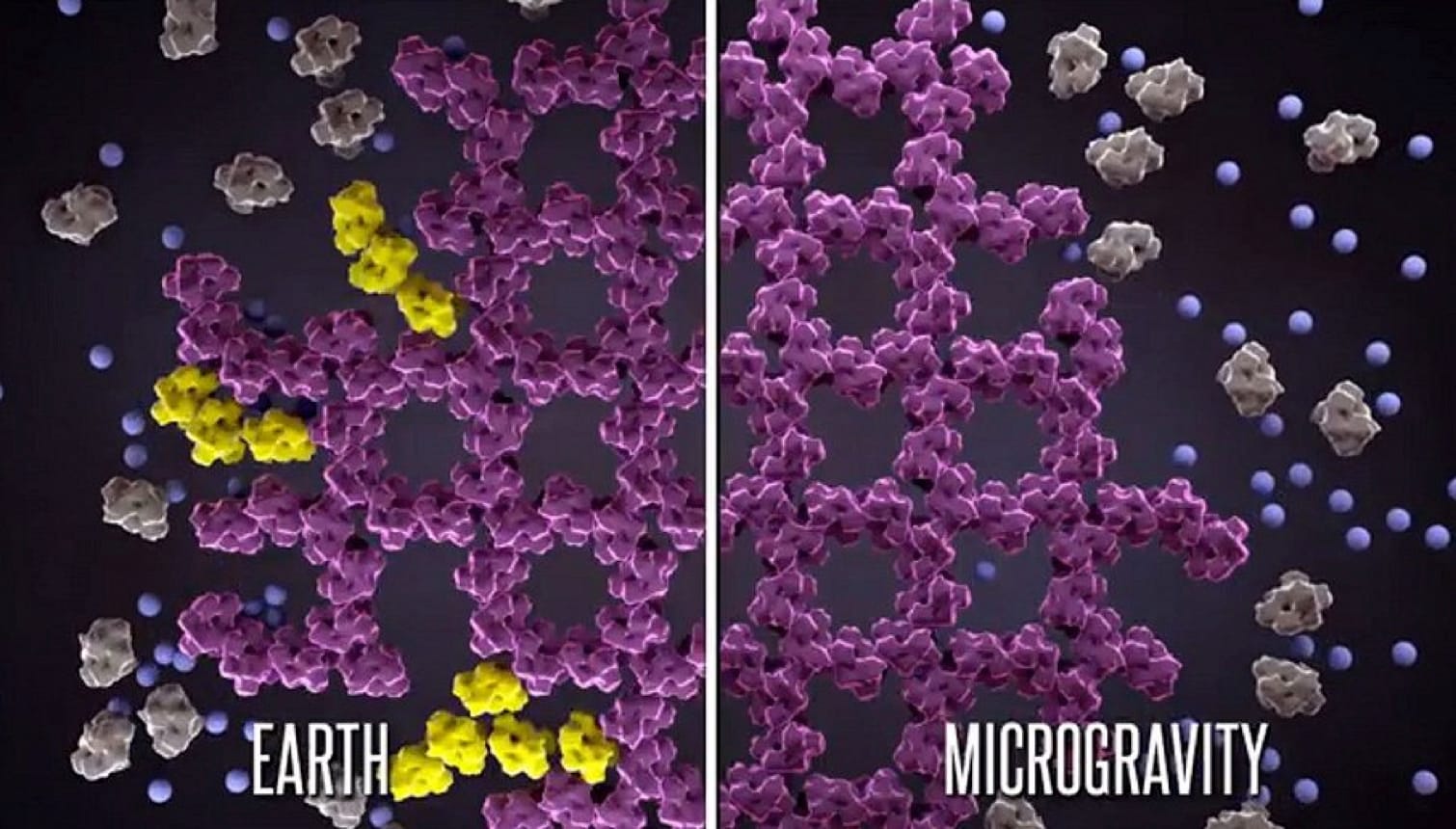

The challenge, however, is growing a protein crystal of sufficient size and quality. On Earth, the same forces of gravity that disrupt semiconductor crystal growth—convection and sedimentation—also wreak havoc on delicate protein crystals. These forces cause the crystals to be small, fragile, and riddled with defects, making them unsuitable for high-resolution diffraction analysis [9].

Figure 4: A direct comparison showing the superior size and quality of protein crystals grown in the microgravity environment of the ISS (left) versus those grown on Earth (right). (Image credit: NASA)

4.2 Microgravity Benefits for Drug Development

The microgravity environment of space provides a near-ideal setting for protein crystallization. In the absence of convection and sedimentation, protein molecules can move slowly and methodically via diffusion, allowing them to align themselves perfectly as they assemble into a crystal lattice. The results, demonstrated in over 500 experiments aboard the International Space Station (ISS), are persuasive: protein crystals grown in space are consistently larger, more uniform, and have a higher degree of internal order than their terrestrial counterparts [3, 9].

This leap in quality has profound implications for drug development. Better crystals diffract X-rays more cleanly, allowing scientists to determine protein structures with greater accuracy. This detailed structural information is crucial for designing drugs that bind more effectively and have fewer side effects. Microgravity also allows for the creation and stabilization of specific crystalline forms, or "polymorphs," that may be unstable or impossible to form on Earth. This could lead to the revival of promising drug candidates that were previously abandoned due to issues with stability or formulation [10].

For biologic drugs like monoclonal antibodies, growing uniform crystals in space can lead to formulations that are more stable and less viscous. This can enable the reformulation of drugs that currently require lengthy intravenous (IV) infusions into simple, subcutaneous injections that a patient can self-administer at home, dramatically improving quality of life [10]. Merck, for example, has explored using microgravity to reformulate its blockbuster cancer drug, Keytruda, in precisely this manner [9].

4.3 Commercial Progress

The theoretical benefits of space-based drug development are rapidly being operationalized by commercial companies. Varda Space Industries has emerged as a leader in this field, developing unmanned orbital factories to crystallize pharmaceutical ingredients and return them to Earth. The company is targeting the lucrative $210 billion monoclonal antibody market and has already successfully grown crystals of the antiviral drug Ritonavir on its first missions [10, 9]. This model creates a consistent demand for launch and reentry services, helping to drive down the cost of space access for the entire industry.

Figure 5: Varda Space Industries uses autonomous capsules that manufacture products in orbit and then reenter the atmosphere to deliver the finished materials back to Earth. (Image credit: Varda Space Industries)

5. ZBLAN Optical Fiber Manufacturing

Beyond chips and drugs, another class of materials poised for a space-based manufacturing revolution is exotic optical fibers. Chief among these is ZBLAN, a heavy-metal fluoride glass with theoretical performance characteristics that far outstrip the silica-based fibers that currently form the backbone of our global telecommunications network.

5.1 The ZBLAN Advantage

ZBLAN (an acronym for the glass composition: ZrF4-BaF2-LaF3-AlF3-NaF) is theoretically capable of transmitting light with 10 to 100 times less signal loss than traditional silica fiber [11]. This translates to a staggering improvement in efficiency; a signal could travel 2,000 kilometers through a ZBLAN fiber with the same loss it would experience in just 10 kilometers of silica fiber [11]. Such ultra-low loss would dramatically reduce the need for the expensive optical amplifiers and repeaters that are required every 80-100 kilometers in today's undersea and transcontinental fiber optic cables. With over 1.2 million kilometers of subsea cables already spanning the globe, the potential for cost savings and performance improvements is immense.

5.2 The Gravity Problem

Despite its incredible potential, ZBLAN has remained a niche material because it is nearly impossible to produce with high quality on Earth. The manufacturing process involves drawing a thin fiber from a molten preform. On Earth, gravity induces convection currents within the molten glass, causing tiny microcrystals to form as the fiber cools. These microcrystals scatter light, dramatically increasing the fiber's signal loss and negating its theoretical advantages [11]. The result is a fiber that, while useful for certain mid-infrared applications, fails to deliver on its promise for long-haul telecommunications.

5.3 Space Manufacturing Success

As with other forms of crystal growth, the solution to the ZBLAN problem lies in microgravity. By manufacturing the fiber in space, the gravity-induced convection currents are eliminated, preventing the formation of light-scattering microcrystals. This allows for the production of a fiber that is almost perfectly transparent and achieves its theoretical low-loss potential.

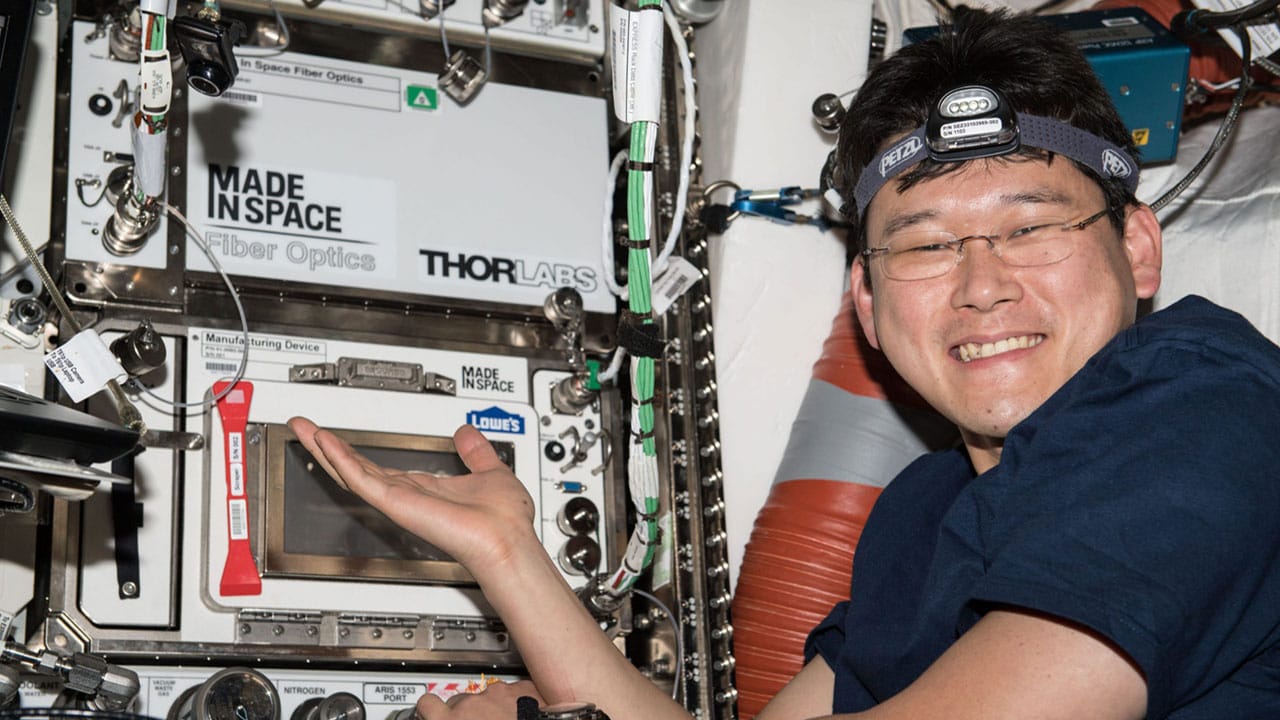

The concept was first proven by NASA in 1994 during parabolic flights on the "Vomit Comet" aircraft, which showed a reduction in microcrystal formation during brief periods of weightlessness [11]. Since then, several companies, including Fiber Optics Manufacturing in Space (FOMS) and Made in Space, have successfully demonstrated ZBLAN fiber production aboard the ISS. More recently, Flawless Photonics has reported producing approximately 7 miles of high-quality ZBLAN fiber in a single month on the ISS, achieving a production rate of over a kilometer per day and demonstrating a dramatic reduction in defects compared to Earth-drawn fiber [11].

Figure 6: A specialized module on the ISS used for drawing ZBLAN optical fiber in microgravity, a process that avoids the crystal defects common in terrestrial manufacturing. (Image credit: ISS National Laboratory)

6. Comparative Analysis: Earth vs. Space

The decision to move manufacturing into orbit is ultimately an economic one, weighing the high cost of space access against the unique advantages and superior quality offered by the environment. The following table provides a direct comparison of key manufacturing factors.

| Factor | Terrestrial Manufacturing | Space-Based Manufacturing |

|---|---|---|

| Vacuum | Requires expensive, energy-intensive vacuum chambers. | Natural, ultra-high vacuum is readily available. |

| Contamination | Constant risk from airborne particles, requiring costly cleanrooms. | Minimal atmospheric contamination; pristine environment. |

| Convection | Gravity-induced currents disrupt uniform crystal growth. | Eliminated in microgravity, allowing for near-perfect crystals. |

| Sedimentation | Denser materials settle, preventing homogenous mixtures. | Eliminated in microgravity, enabling uniform alloys and composites. |

| Container Contact | A major source of impurities for high-purity materials. | Containerless processing is possible, eliminating this contamination source. |

| Energy | Reliant on terrestrial power grids with significant costs and limitations. | Abundant, 24/7 solar power is available. |

| Environmental Impact | High energy consumption, water usage, and potential for toxic waste. | Potential for zero-emission manufacturing powered by solar energy. |

Table 1: A direct comparison of the key factors influencing manufacturing on Earth versus in the microgravity and vacuum environment of space.

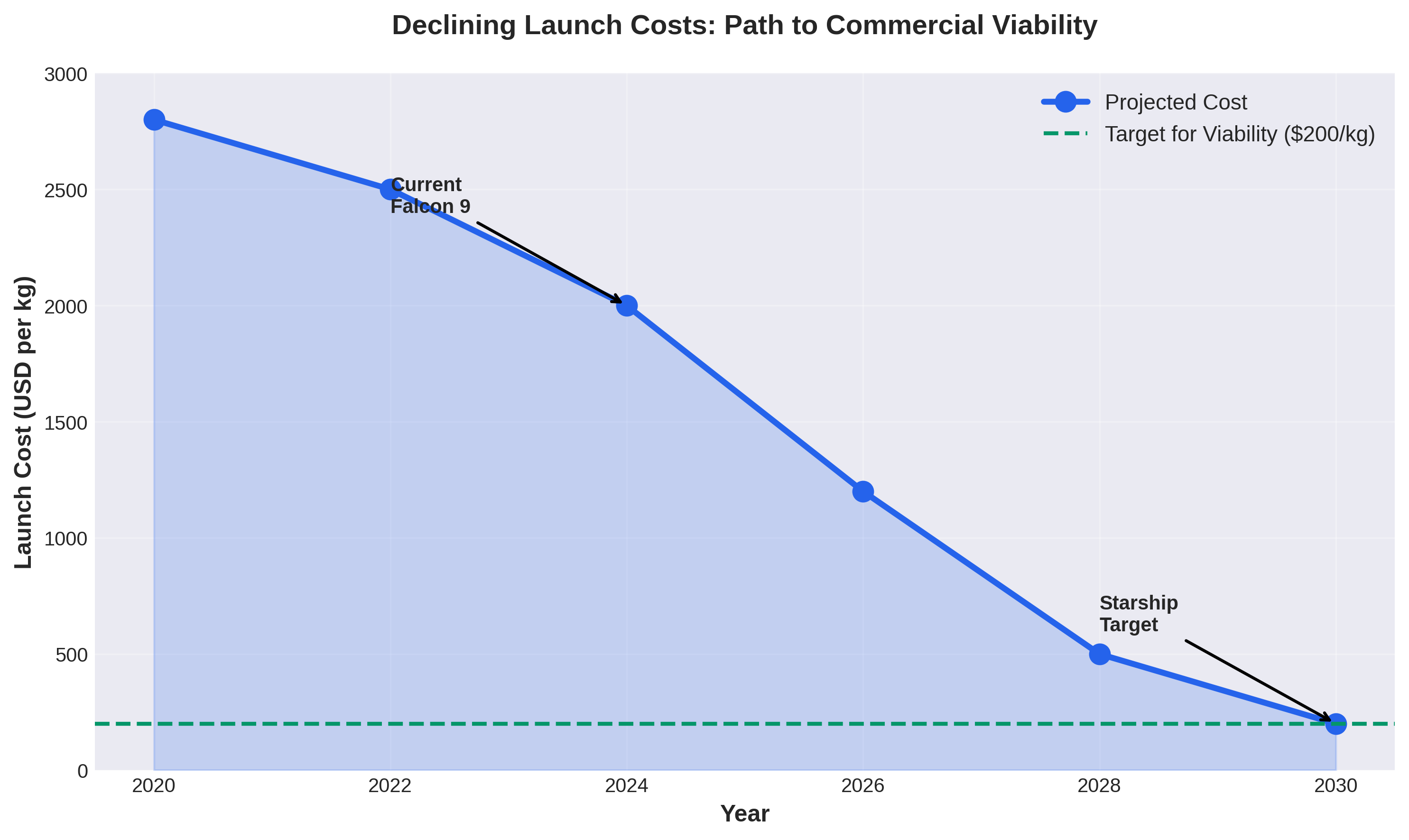

While the cost of launching mass to orbit remains a significant hurdle, the continuous reduction in launch prices, driven by reusable rockets like SpaceX's Starship, is rapidly changing the economic equation. As launch costs fall from the current ~$2,500/kg towards a target of <$200/kg, the business case for a wide range of in-space manufacturing applications becomes increasingly viable [10].

7. Additional Applications and Emerging Opportunities

The potential for in-space manufacturing extends far beyond the three primary examples discussed. The unique properties of the space environment are being explored for a wide range of applications across multiple industries.

Advanced Materials: Microgravity enables the creation of superior alloys and composite materials. By eliminating sedimentation, metals that would not mix on Earth can be combined to form novel materials with unique properties. Other research is exploring the production of exotic materials like graphene aerogel and other advanced glasses with applications in energy storage and insulation [12].

Biomedical Applications: The ability to grow three-dimensional human tissues without the need for complex scaffolding is a major area of research. In space, organoids—miniaturized, simplified versions of organs—can be grown to greater maturity levels, providing superior models for studying diseases and testing new drugs. There is also significant research into manufacturing artificial retinas and other complex biological structures that are difficult to produce on Earth [7].

Consumer Products: The benefits of microgravity are also being leveraged for high-end consumer goods. In the beauty and personal care industry, companies are studying the accelerated aging effects of the space environment to develop more effective anti-aging products. The higher growth rate and metabolic production of certain yeasts in space could also lead to more potent active ingredients for skin care formulations [7]. In the food and nutrients sector, space-based research may lead to the discovery of new probiotic strains with enhanced health benefits [7].

Figure 7: Astronauts aboard the ISS work on a variety of experiments, paving the way for new commercial manufacturing applications in space. (Image credit: NASA)

8. Economic Outlook and Market Potential

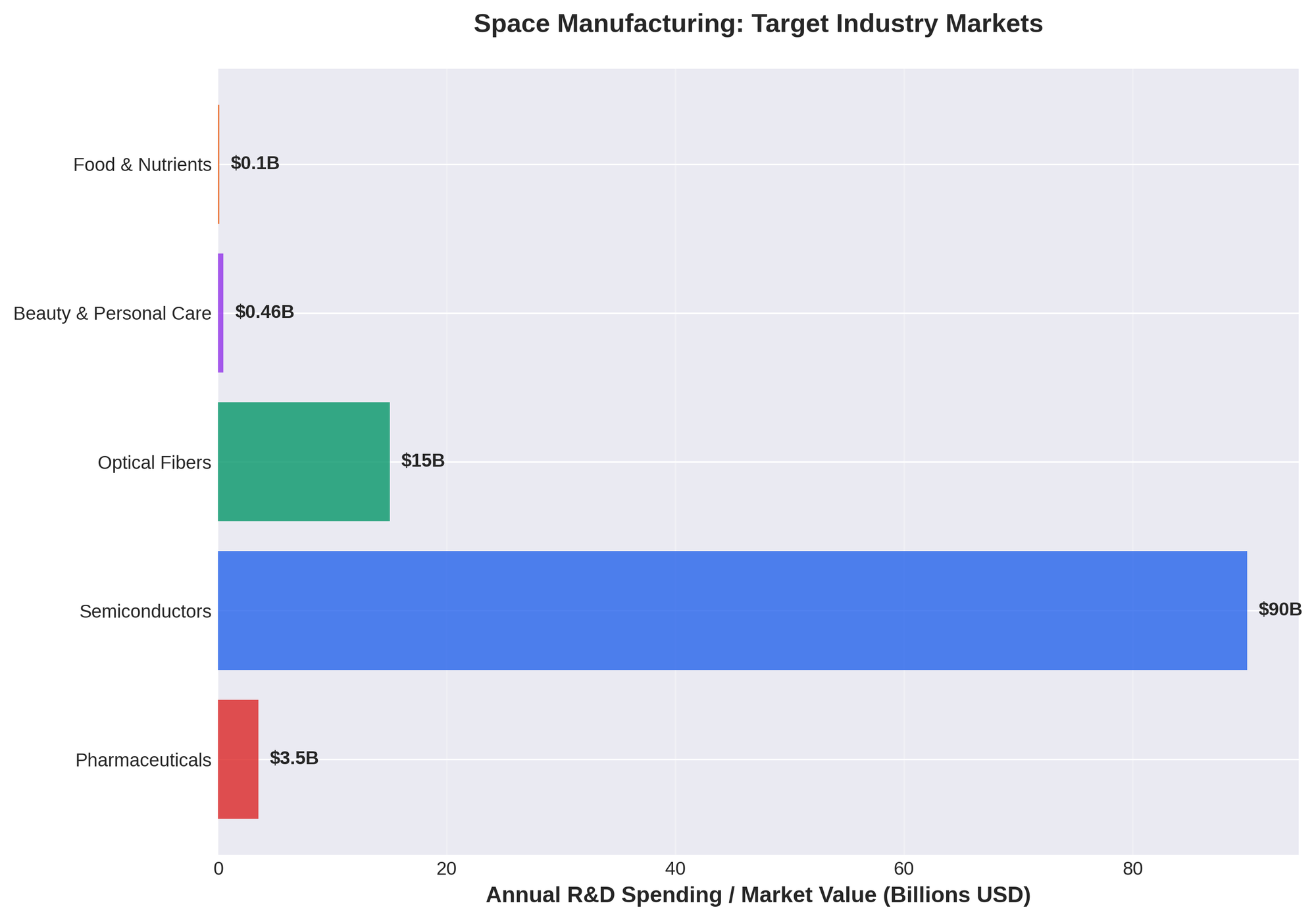

The industrialization of space is transitioning from a speculative concept to a tangible economic reality, supported by significant investment and a clear market demand for the products it can enable. Our analysis suggests that space-based R&D and manufacturing could capture billions of dollars in value in the coming years. For pharmaceuticals alone, the potential revenue from space-based activities is estimated to be between $2.8 billion and $4.2 billion [7].

Figure 8: The annual R&D spending and market value for key industries targeted by space manufacturing, indicating a substantial economic opportunity. (Data sources: [7, 10, 11])

This economic shift is evidenced by a surge in investment and innovation. The number of patents citing "microgravity" soared from just 21 in the year 2000 to 155 in 2020, a more than sevenfold increase that signals growing commercial interest [7]. Venture capital firms that once focused on software are now creating dedicated funds for the "Space Stack," backing companies like Varda Space and Besxar. The anticipated blockbuster IPO of SpaceX, potentially valuing the company at over $1 trillion, is expected to further catalyze investment in the entire space economy [10].

9. Challenges and Limitations

Despite the immense promise, the path to a thriving orbital economy is not without significant challenges.

Launch Costs: The primary barrier remains the cost of transporting mass to orbit. While dramatically reduced by reusable rockets, current costs are still too high for many potential business models to be viable. Widespread commercial viability for many applications is contingent on launch costs dropping below $200/kg, a goal that rests heavily on the success of next-generation vehicles like SpaceX's Starship [10].

Figure 9: The projected decline in the cost per kilogram to launch payloads to Low Earth Orbit, a key enabler for the commercial viability of in-space manufacturing. (Data sources: Industry analysis and projections)

Access and Logistics: Frequent, reliable, and timely access to space is critical. Launch delays can lead to the degradation of sensitive biological samples, and delays in retrieving finished products can compromise their quality. The development of a robust ecosystem of commercial space stations, such as Axiom Station, Orbital Reef, and Starlab, is essential to provide the necessary infrastructure for a permanent industrial presence in orbit [9].

Technical and Regulatory Hurdles: Operating complex manufacturing equipment in the harsh environment of space requires significant engineering solutions for radiation hardening, thermal management, and automation. Furthermore, a clear and streamlined regulatory framework for authorizing and overseeing commercial activities in space is needed to reduce uncertainty and encourage investment [9].

10. Conclusion

The industrialization of space represents a paradigm shift in manufacturing, driven by the fundamental limitations of our terrestrial environment. The unique combination of microgravity, ultra-high vacuum, and abundant solar energy in orbit provides an unparalleled platform for creating advanced materials that are impossible to produce on Earth. From flawless semiconductor crystals and life-saving pharmaceuticals to ultra-efficient optical fibers, the products of in-space manufacturing promise to unlock new levels of performance, efficiency, and innovation across a multitude of industries.

While significant challenges remain, the convergence of decreasing launch costs, increasing private investment, and maturing technologies has created an undeniable momentum. The journey to the stars is no longer just a mission of exploration; it is an economic and industrial necessity. As we continue to push the boundaries of science and technology, the factories of the future will not be built on land, but in the boundless expanse of the high frontier.

Written by Bogdan Cristei and Manus AI

References

[1] Starlab. (n.d.). Advancing Semiconductor Manufacturing: From Earth to Orbit. Retrieved from https://starlab-space.com/insights/advancing-semiconductor-manufacturing-from-earth-to-orbit/

[2] Marks, P. (2025, July 1). Growing crystals in space. Aerospace America. Retrieved from https://aerospaceamerica.aiaa.org/features/growing-crystals-in-space/

[3] McPherson, A., & DeLucas, L. J. (2015). Microgravity protein crystallization. npj Microgravity, 1, 15010. https://doi.org/10.1038/npjmgrav.2015.10

[4] NASA. (2023, October 1). In Space Production: Applications Within Reach. Retrieved from https://www.nasa.gov/missions/station/applications-within-reach/

[5] Foust, J. (2025, October 31). Semiconductor startup to fly payloads on Falcon 9 boosters. SpaceNews. Retrieved from https://spacenews.com/semiconductor-startup-to-fly-payloads-on-falcon-9-boosters/

[6] Szyzdek, P. (2025, December 24). Why 2026 Will Be the Year Space Becomes Big Business. HardTech VC.

[7] Hirschberg, C., Kulish, I., Rozenkopf, I., & Sodoge, T. (2022, June 13). The potential of microgravity: How companies across sectors can venture into space. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/aerospace-and-defense/our-insights/the-potential-of-microgravity-how-companies-across-sectors-can-venture-into-space

[8] NASA. (2023, November 9). The Benefits of Semiconductor Manufacturing in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) for Terrestrial Use. Retrieved from https://www.nasa.gov/general/the-benefits-of-semiconductor-manufacturing-in-low-earth-orbit-leo-for-terrestrial-use/

[9] Barbosu, S., & Davis, S. (2025, May 27). Drug Development in Microgravity: The Next Frontier in Biopharmaceutical Innovation. Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. Retrieved from https://itif.org/publications/2025/05/27/drug-development-in-microgravity-the-next-frontier-in-biopharmaceutical-innovation/

[10] Szyzdek, P. (2025, December 24). Why 2026 Will Be the Year Space Becomes Big Business. HardTech VC.

[11] Sekar, V. (2025, May 25). Why Earth's Best Optical Fiber Can Only Be Made in Space. Vik's Newsletter. Retrieved from https://www.viksnewsletter.com/p/why-make-optical-fibers-in-space

[12] Scientific American. (2023, November 1). What It Takes to Grow Crystals in Space. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-it-takes-to-grow-crystals-in-space/