From Pixels to Physicality: A Comprehensive Report on Vision-Language Models for Autonomy

Introduction

The field of Artificial Intelligence is undergoing a profound shift, moving beyond the digital realm of text and images into the complex, dynamic environment of the physical world. At the heart of this transition are Vision-Language Models (VLMs), a groundbreaking technology that enables machines to understand and interact with their surroundings in a manner previously confined to the realm of science fiction. For investors, founders, and technologists, understanding this rapidly evolving landscape is no longer optional; it is critical for identifying the generational opportunities and navigating the significant risks that lie ahead.

This report provides a comprehensive overview of VLMs and their application in autonomy, specifically addressing the core questions faced by non-expert stakeholders. We will demystify the technology, assess the current state of development, and illuminate the path to commercial viability. Our goal is to provide the clarity needed to distinguish between ambitious demos and deployable reality, and to equip you with a framework for evaluating the risk, reward, and capital intensity of this transformative field.

We will explore the foundational concepts, from the basic architecture of VLMs to the emergence of more advanced Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models. We will delve into the critical concepts of Spatial Intelligence and Embodied Reasoning, which represent the next frontier in AI. Finally, we will analyze the "deployment gap" that separates laboratory success from real-world commercialization, offering a pragmatic guide for investors seeking to navigate this exciting but challenging new domain.

1. The Dawn of Physical AI: Understanding Vision-Language Models

A Vision-Language Model (VLM) is a type of AI model that can process and understand information from both images (vision) and text (language) simultaneously. This integration of two distinct data modalities allows VLMs to perform tasks that neither a pure computer vision model nor a pure language model could accomplish alone. At its core, a VLM learns to create a shared representation of concepts, linking the visual appearance of an object, like a red apple, with its textual description, "a red apple." [1]

The foundational technology that enabled this breakthrough is contrastive learning. A key example is OpenAI's CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) model. CLIP is trained on a massive dataset of image-text pairs scraped from the internet. During training, the model is shown an image and a set of text snippets, one of which is the correct description of the image. The model's goal is to learn to associate the correct image-text pair and push the incorrect pairs further apart in its internal representation space. [2] This process forces the model to learn a rich, multi-modal understanding of the world.

This shared embedding space is the crucial innovation. It allows the model to perform zero-shot classification, meaning it can identify objects in an image that it has never been explicitly trained to recognize. For example, a VLM trained on a general dataset can identify a specific dog breed without ever having been trained on a dataset of dog breeds. It does this by comparing the image of the dog to the text descriptions of different breeds and finding the closest match in its learned embedding space.

Core Architectural Components

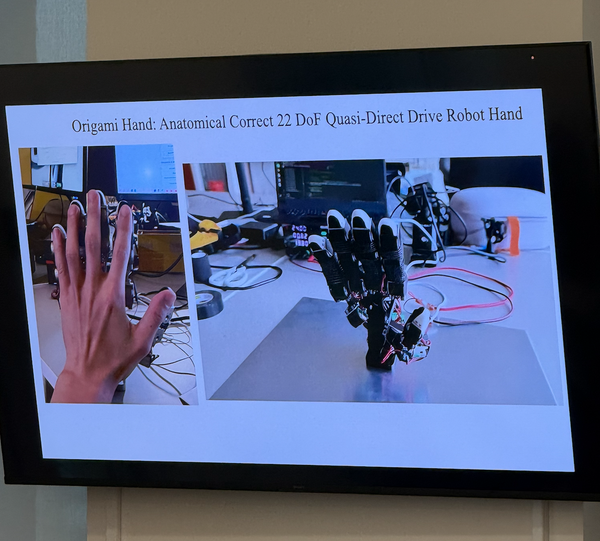

A typical VLM consists of two main components. The evolution from this basic VLM structure to a more capable Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model is a crucial conceptual leap, as illustrated below:

A diagram illustrating the architectural evolution from a descriptive Vision-Language Model (VLM) to a functional Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model.

A typical VLM consists of two main components:

- Vision Encoder: A neural network, typically a Vision Transformer (ViT) or a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), that processes an input image and converts it into a numerical representation (embedding).

- Language Encoder: A Transformer-based neural network (like BERT or GPT) that processes input text and converts it into a similar numerical representation (embedding).

The embeddings from both encoders are then projected into a shared, multi-modal embedding space where they can be compared and combined. This architecture allows VLMs to perform a wide range of tasks, including:

- Image Captioning: Generating a text description of an image.

- Visual Question Answering (VQA): Answering questions about an image.

- Image Retrieval: Finding images that match a text description.

While these capabilities are powerful, they are primarily descriptive. They allow the AI to understand the world, but not to act within it. This limitation is what led to the development of the next evolution: Vision-Language-Action models.

2. From Understanding to Action: The Rise of VLA Models

The true potential of AI in the physical world is unlocked when models can not only perceive and understand but also take action. This is the domain of Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models. VLAs are an evolution of VLMs, extending the architecture to include a third modality: action. Instead of just outputting text, a VLA can output a sequence of actions that can be used to control a robot.

Google's RT-2 (Robotics Transformer 2) is a prime example of a VLA model. RT-2 leverages a powerful, pre-trained VLM (like PaLM-E) and fine-tunes it on a dataset of robot trajectories. [3] This process teaches the model to map visual and language inputs to robotic actions. The actions are represented as tokens, just like words in a sentence, and the model learns to generate a sequence of action tokens that correspond to a specific task.

For example, if you give RT-2 the command, "pick up the apple," it will process the image of the scene, identify the apple, and then generate a sequence of action tokens that instruct the robot arm to move to the apple, grasp it, and lift it. This is a significant leap from a VLM, which could only describe the scene or answer questions about it.

The key insight behind VLA models is that the knowledge learned from vast amounts of internet data (text and images) can be transferred to the domain of robotics. The VLM provides the model with a foundational understanding of the world—what objects are, how they relate to each other, and what human language means. The robotics data then grounds this knowledge in the physical world, teaching the model how to translate its understanding into action.

The Power of Generalization

The most significant advantage of VLA models is their ability to generalize to new tasks, objects, and environments. Because they are built on top of powerful VLMs, they can understand and reason about concepts they have never encountered during their robotics training. For example, RT-2 was able to perform tasks like picking up a ball and putting it in a basket, even though it had never been explicitly trained on this specific task. It was able to reason that a "ball" is an object that can be picked up and a "basket" is a container that can hold objects, and then generate the appropriate sequence of actions.

This ability to generalize is what makes VLA models so promising for real-world applications. Instead of programming a robot for every single task it needs to perform, we can train a single VLA model that can adapt to a wide range of situations. This dramatically reduces the cost and complexity of deploying robots in dynamic environments like warehouses, hospitals, and homes.

The Genealogy of Key Models

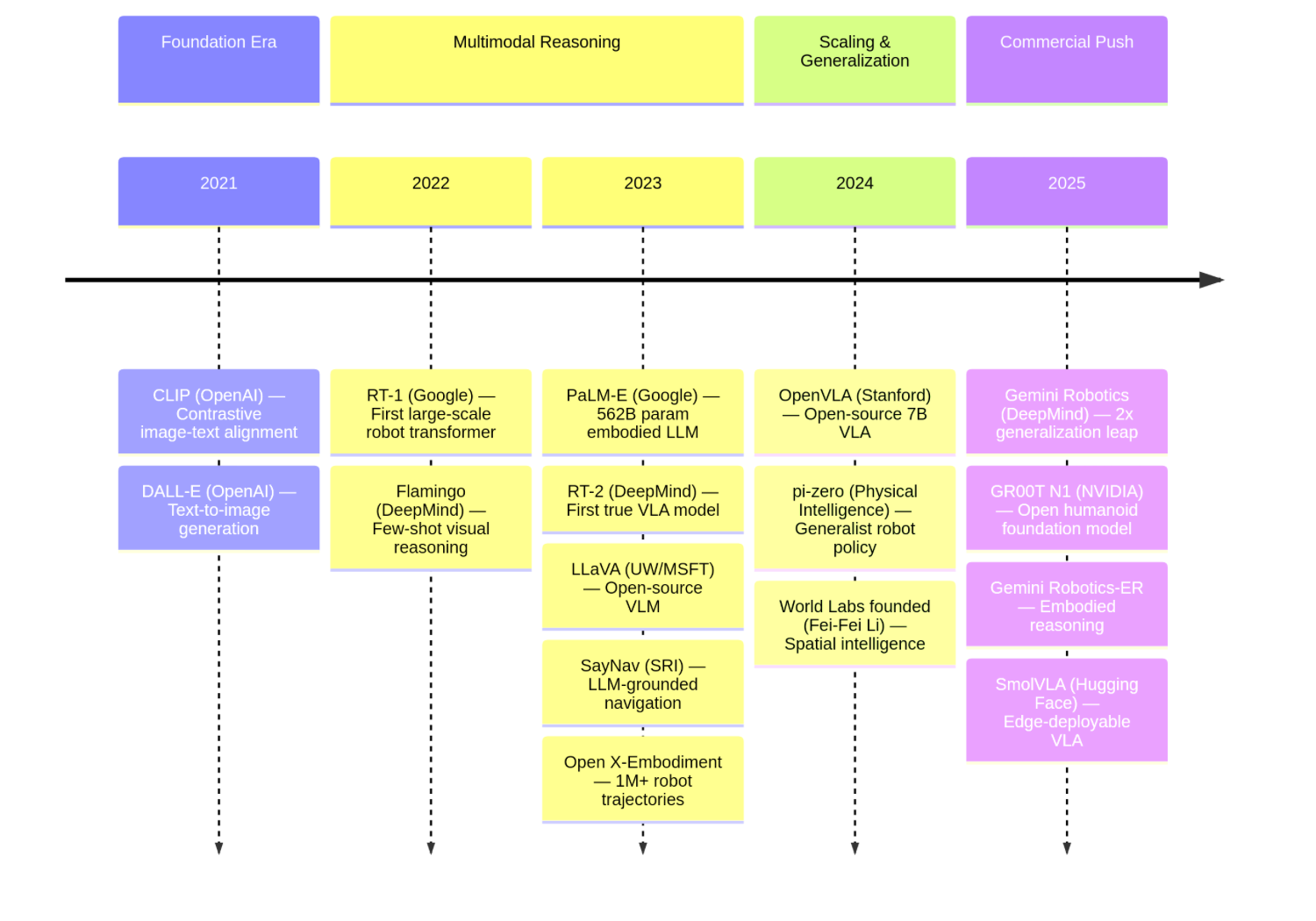

Evolution of Vision-Language Models for Autonomy (2021-2025)

A timeline illustrating the rapid evolution of key models, from foundational research in 2021 to the push for commercial, general-purpose systems in 2025.

The field has evolved rapidly, with each generation of models building on the insights of the last. The following genealogy of the most important models, from foundational VLMs to the latest VLAs, helps orient the reader on the state of the art.

CLIP (OpenAI, 2021): A foundational VLM that introduced contrastive learning to align images and text in a shared embedding space, becoming a building block for most subsequent models. [2]

RT-1 (Google, 2022): One of the first large-scale VLA models to directly map camera images and language instructions to robot actions using a Transformer architecture.

PaLM-E (Google, 2023): A 562-billion parameter VLM that integrates sensor data directly into a language model, enabling it to reason about the physical world.

LLaVA (UW-Madison / Microsoft, 2023): A VLM that demonstrated a powerful model could be built by connecting a CLIP vision encoder to a large language model (Vicuna) with a simple projection layer, making VLMs more accessible.

RT-2 (Google DeepMind, 2023): A VLA that showed a pre-trained VLM could be fine-tuned to output robot actions, effectively transferring web-scale knowledge to robotic control. [3]

Open X-Embodiment / RT-X (Google + 21 Institutions, 2023): A dataset and VLA project that created the largest open-source real robot dataset (1M+ trajectories, 22 robot types), demonstrating cross-embodiment generalization. [16]

OpenVLA (Stanford / UC Berkeley, 2024): An open-source 7B parameter VLA model, making foundation model-based robot control accessible to the broader academic community.

π0 (Pi-Zero) (Physical Intelligence, 2024): A generalist VLA policy model that outperformed prior VLAs on diverse manipulation tasks, demonstrating the viability of a single model for many different robots and tasks. [12]

GR00T N1 (NVIDIA, 2025): An open foundation model for humanoid robots with a dual-system architecture, trained on human videos, real and simulated robot data. [17]

Gemini Robotics (Google DeepMind, 2025): A VLA built on Gemini 2.0 that more than doubled performance on generalization benchmarks compared to other state-of-the-art VLAs. [5]

Gemini Robotics-ER (Google DeepMind, 2025): An advanced, embodied VLM with enhanced spatial reasoning, achieving a 2-3x success rate vs. Gemini 2.0 in end-to-end robotic settings. [5]

This rapid pace of development is a key reason for the excitement in the investment community. However, it is important to note that most of these models have been demonstrated primarily in controlled lab settings. The gap between benchmark performance and real-world deployment remains the central challenge, as we will explore in detail later in this report.

3. The Next Frontier: Spatial Intelligence and Embodied Reasoning

While VLA models represent a major step forward, they still face limitations in their ability to truly understand and navigate the complexities of the physical world. This has led to the emergence of two closely related concepts that are shaping the future of robotics: Spatial Intelligence and Embodied Reasoning.

Spatial Intelligence, a term championed by AI pioneer Dr. Fei-Fei Li, refers to an AI's ability to perceive, reason about, and interact with the three-dimensional world. [4] It goes beyond simple object recognition to encompass an intuitive understanding of spatial relationships, physics, and causality. As Dr. Li puts it, current LLMs are like "wordsmiths in the dark; eloquent but inexperienced, knowledgeable but ungrounded." [4] They can describe a picture of a coffee mug, but they don't truly understand that it's a container, that it can hold liquid, or that it needs to be grasped by the handle. Spatial intelligence is the missing piece that connects abstract knowledge to physical reality.

Embodied Reasoning, a term used by Google DeepMind, is a similar concept that emphasizes the importance of having a physical body (an "embodiment") to learn and reason about the world. [5] The idea is that true intelligence cannot be developed in a disembodied state, purely from processing data. It requires interaction with the environment, learning from trial and error, and experiencing the consequences of one's actions. Google's Gemini Robotics-ER model is a prime example of this approach. It is designed to enhance Gemini's spatial understanding and reasoning capabilities, allowing it to perform complex tasks that require a deep understanding of the physical world, such as intuiting the correct way to grasp an object or planning a safe path through a cluttered room. [5]

These concepts are not just academic curiosities; they are the driving force behind the next generation of robotics companies. Dr. Li's startup, World Labs, is building frontier models for 3D world perception, generation, and interaction, and has already attracted significant investment. [6] Similarly, Google's partnership with Apptronik to develop humanoid robots powered by Gemini is a clear indication of the industry's commitment to embodied AI. [5]

A Practical Example: SayNav and Robot Navigation

To make these abstract concepts concrete, consider the SayNav system developed by researchers at SRI International, a storied institution that has been at the forefront of AI since the 1960s (it created Shakey, the first mobile robot with the ability to perceive and reason about its surroundings, and later gave birth to Siri). [18]

SayNav tackles a fundamental challenge in robotics: how does a robot navigate to a specific location in a large, unfamiliar building? Traditional approaches require a complete, pre-built map of the environment. SayNav takes a radically different approach by leveraging the common-sense knowledge embedded in a Large Language Model. [18]

Here is how it works: imagine you tell a robot, "Go to the kitchen and get me a glass of water." The robot has never been in this building before. SayNav uses an LLM to generate a high-level plan based on common-sense reasoning. It knows that kitchens are typically found near dining areas, that glasses are usually in cabinets, and that water comes from a faucet. As the robot explores, it builds a dynamic map of the environment, grounding the LLM's abstract knowledge in the specific layout of the building. This combination of abstract reasoning and real-time perception is the essence of spatial intelligence in action.

This is precisely the kind of technology that is being developed by startups working at the intersection of VLMs and robotics. The founder referenced in the text messages that prompted this report described his company's work as "Spatial Intelligence" or "Spatial Reasoning," noting that "Google started calling it Embodied Reasoning." [7] This convergence of terminology from both the startup world and the tech giants is a strong signal that this is a critical area of development.

4. The Hard Reality: Bridging the Deployment Gap

For an investor, the most critical question is not whether the technology is impressive, but whether it is deployable and profitable. This is where the "deployment gap" comes into play—the significant chasm between a compelling demo in a controlled lab environment and a reliable, scalable product in the messy real world. As one investor noted, "in visual language models and robotics, it is super hard to understand 'what needs to happen' for commerce to begin." [7] This section breaks down the key obstacles that constitute this gap, drawing heavily on the analysis of venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz (a16z). [8]

"The deployment gap is where research meets reality, where capabilities become capacity, and where performance on benchmarks translate to hard power. If we are to build a world with orders of magnitude more robots... we will have to build the essential infrastructure that transforms impressive demos into reliable and scalable systems." — Oliver Hsu, a16z [8]

The Core Challenges of Deployment

The significant gap between controlled lab environments and the realities of commercial deployment, highlighting the six core challenges identified by a16z.

The transition from a research prototype to a commercial product is fraught with challenges that are often underestimated by those outside the field. These are not minor engineering hurdles; they are fundamental problems that require significant investment and innovation to overcome.

Distribution Shift

Description: Models trained in a lab or on simulation data fail to perform well in the real world due to unexpected variations in lighting, object appearance, and environment. A model with 95% accuracy in the lab might only achieve 60% in a real warehouse. [8]

Impact on Commercial Viability: Unpredictable performance leads to high failure rates, requiring costly human intervention and undermining the economic case for automation.

Reliability Thresholds

Description: Research optimizes for average performance, but commercial applications require near-perfect reliability (99.9%+). A 1% failure rate that is acceptable in a lab setting is catastrophic for a robot operating thousands of cycles per day. [8]

Impact on Commercial Viability: Frequent failures erode customer trust, increase operational costs, and can pose significant safety risks.

Latency vs. Capability

Description: The most powerful VLA models are often too large and slow to run on the edge hardware of a robot, which needs to make decisions in real-time (20-100Hz). Running the model in the cloud introduces unacceptable latency. [8]

Impact on Commercial Viability: A trade-off must be made between the model's intelligence and its ability to react quickly, limiting the complexity of tasks the robot can perform.

Integration Complexity

Description: A robot does not operate in a vacuum. It must integrate with a customer's existing systems, such as Warehouse Management Systems (WMS), fleet coordination software, and safety protocols. These integrations are complex and costly. [8]

Impact on Commercial Viability: High integration costs and long deployment times can make the total cost of ownership prohibitive for many customers, limiting the addressable market.

Safety & Certification

Description: Existing safety standards (e.g., ISO 10218) were written for predictable, programmed robots, not for AI-driven systems whose behavior emerges from training data. Certifying a large, non-deterministic model is a major, unsolved challenge. [8]

Impact on Commercial Viability: The lack of clear certification pathways creates significant legal and regulatory uncertainty, slowing down adoption and increasing liability for both manufacturers and customers.

Maintenance

Description: When a learned policy fails, it cannot be debugged like traditional software. There is no code to inspect, only a vast matrix of weights. Diagnosing and fixing problems requires a new set of skills and tools that are not yet widely available. [8]

Impact on Commercial Viability: High maintenance costs and the need for specialized talent increase the operational burden on the customer, reducing the overall ROI.

These challenges do not exist in isolation; they compound each other. As a16z notes, distribution shift causes failures, which require human intervention, which drives up costs, which limits the scale of deployment, which in turn limits the amount of real-world data that can be collected to address the distribution shift in the first place. [8] This vicious cycle is a major barrier to commercialization.

5. The Path to Commercialization: From Lab to Loading Dock

Closing the deployment gap is not a matter of waiting for a single, magical breakthrough. Rather, it will require a concerted effort across multiple fronts, building the infrastructure and tooling necessary to make physical AI a reality. For investors, the companies building these enabling technologies represent a significant, and potentially less risky, investment opportunity than the robot manufacturers themselves.

Key Areas for Investment and Innovation

- Deployment-Distribution Data: The most critical ingredient for closing the gap is data—massive amounts of it, collected from real-world environments. This is the "robotics data flywheel" effect: the more robots are deployed, the more data they collect, which in turn improves the models and enables more deployments. Companies that are building the infrastructure for scalable data collection, annotation, and management are creating a foundational asset for the entire industry. This includes teleoperation platforms for remote data gathering and on-device data collection systems that allow robots to learn while they work. [8]

- Reliability Engineering for Learned Systems: A new discipline of engineering is emerging to address the unique challenges of making AI systems reliable. This includes developing methods for characterizing failure modes, creating hybrid architectures that combine learned policies with programmed fallbacks, and building runtime monitoring systems that can detect distribution shift in real-time. [8] Companies that are creating the "DevOps for robotics" will be essential for ensuring the safety and reliability of deployed systems.

- Edge-Deployable Models: The trade-off between latency and capability must be addressed. This requires developing new, more efficient model architectures that are designed specifically for the constraints of robotic hardware. Models like Hugging Face's SmolVLA (450M parameters) and Google's Gemini Robotics On-Device are examples of this trend. [8] Investment in hardware-software co-design, where chips and models are developed in tandem, will also be crucial.

- Integration Infrastructure: The complexity of integrating robots into existing enterprise systems is a major bottleneck. There is a significant opportunity for companies that can create a "middleware" layer for robotics, providing standardized adapters for common WMS, MES, and ERP platforms, as well as tools for fleet coordination and observability. [8]

- Safety Frameworks for Learned Systems: The development of new safety standards and certification processes for AI-driven robots is a critical, albeit less glamorous, area of need. This will involve a combination of technical solutions (e.g., runtime safety layers) and institutional collaboration between industry, government, and academia. [8]

As robotics pioneer Rodney Brooks advises, the most successful robot companies will be those that can leverage existing infrastructure and supply chains, rather than requiring customers to make significant upfront investments. [9] The Roomba succeeded not just because of its cleaning capabilities, but because it worked out of the box with no setup other than plugging it into a standard electrical outlet. The same principle applies to the next generation of robots.

6. Commercial Context and Forward Outlook

The technical progress in VLMs and VLAs has ignited a wave of commercial activity and investment. While a detailed market analysis is beyond the scope of this technical primer, it is important to acknowledge the significant capital flowing into the space. Startups like Figure AI (humanoid robots), Physical Intelligence (robot foundation models), and World Labs (spatial intelligence) are attracting valuations in the billions, while established giants like Google, NVIDIA, and Tesla are making massive investments in both research and deployment. [6] [11] [12] This capital influx is a strong signal of the perceived transformative potential of physical AI, but it also creates immense pressure to bridge the deployment gap and find commercially viable applications. The journey from a compelling demo to a profitable product remains long and arduous, as evidenced by the more than a decade of development and tens of billions of dollars invested in the autonomous driving sector. [10]

7. Conclusion: The Road Ahead

The journey from pixels to physicality is well underway. Vision-Language Models have provided the foundational ability for machines to see and understand, while the evolution to Vision-Language-Action models has given them the means to act. The pursuit of Spatial Intelligence and Embodied Reasoning now represents the critical next phase, seeking to imbue these systems with the common-sense understanding of the physical world that humans take for granted.

The primary obstacle is no longer a lack of capability in a controlled lab, but the immense challenge of bridging the deployment gap. Reliability, safety, and scalability in the chaotic, unpredictable real world are the core problems that must be solved. Success will not come from a single breakthrough model, but from the painstaking work of building the infrastructure, tooling, and engineering discipline required to make these systems robust and trustworthy.

For technologists and investors alike, the most promising areas are not just the companies building the robots themselves, but those creating the enabling infrastructure—the "picks and shovels" for the gold rush. The path to commercialization is paved with opportunities in data collection, reliability engineering, edge-deployable models, and safety certification. The ultimate winners will be those who understand that the journey from a captivating demo to a profitable product is the hardest, and most valuable, part of the process.

References

[1] IBM Technology, "What are vision language models?" (https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/vision-language-models)

[2] OpenAI, "CLIP: Connecting Text and Images" (https://openai.com/index/clip/)

[3] Google DeepMind, "RT-2: New model translates vision and language into action" (https://deepmind.google/blog/rt-2-new-model-translates-vision-and-language-into-action/)

[4] Dr. Fei-Fei Li, "From Words to Worlds: The Rise of Spatial Intelligence" (https://drfeifei.substack.com/p/from-words-to-worlds-spatial-intelligence)

[5] Google DeepMind, "Gemini Robotics brings AI into the physical world" (https://deepmind.google/blog/gemini-robotics-brings-ai-into-the-physical-world/)

[6] Reuters, "AI godmother Fei-Fei Li raises $230 million to launch AI startup" (https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/ai-godmother-fei-fei-li-raises-230-million-launch-ai-startup-2024-09-13/)

[7] User-provided text messages, February 2026.

[8] Andreessen Horowitz, "The Physical AI Deployment Gap" (https://www.a16z.news/p/the-physical-ai-deployment-gap)

[9] Rodney Brooks, "Tips for Building and Deploying Robots" (https://rodneybrooks.com/tips-for-building-and-deploying-robots/)

[10] TechCrunch, "Waymo raises $16 billion round to scale robotaxi fleet to London, Tokyo" (https://techcrunch.com/2026/02/02/waymo-raises-16-billion-round-to-scale-robotaxi-fleet-london-tokyo/)

[11] Bloomberg, "Robotics Startup Figure AI in Talks for New Funding at $39.5 Billion Valuation" (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-02-14/robotics-startup-figure-ai-in-talks-for-new-funding-at-39-5-billion-valuation)

[12] Physical Intelligence, "Physical Intelligence raises $600M Series B to build generalist robot policies" (https://www.physicalintelligence.ai/news/series-b)

[13] The Verge, "Tesla begins offering unsupervised robotaxi rides in Austin" (https://www.theverge.com/transportation/866165/tesla-robotaxi-unsupervised-austin-texas-safety-monitor)

[14] Fortune Business Insights, "Autonomous Vehicle Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis" (https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/autonomous-vehicle-market-109045)

[15] Goldman Sachs, "The Global Market for Robots Could Reach $38 Billion by 2035" (https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/the-global-market-for-robots-could-reach-38-billion-by-2035)

[16] Google DeepMind, "Scaling up learning across many different robot types" (https://deepmind.google/blog/scaling-up-learning-across-many-different-robot-types/)

[17] NVIDIA, "NVIDIA Introduces GR00T N1, a Foundation Model for Humanoid Robots" (https://nvidianews.nvidia.com/news/nvidia-introduces-groot-n1-a-foundation-model-for-humanoid-robots)

[18] SRI International, "SayNav: Grounding Large Language Models to Navigation in New Environments" (https://www.sri.com/ics/computer-vision/saynav-grounding-large-language-models-to-navigation-in-new-environments/)

[19] J.P. Morgan Asset Management, "Is robotics the next frontier for AI?" (https://am.jpmorgan.com/hk/en/asset-management/per/insights/market-insights/market-updates/on-the-minds-of-investors/is-robotics-the-next-frontier-for-ai/)

[20] Crunchbase News, "Big AI Funding Trends To Watch In 2026" (https://news.crunchbase.com/ai/big-funding-trends-charts-eoy-2025/)

[21] Andreessen Horowitz, "AI for the Physical World" (https://a16z.com/ai-for-the-physical-world/

Written by Bogdan Cristei and Manus AI