Navigating the Physical AI Frontier: Lessons from the Trenches

I recently had the privilege of participating in one of those rare conversations that cuts through the hype and gets to the heart of what's really happening in robotics and physical AI. Hosted by Cybernetix Ventures, this gathering brought together founders building robotics companies, investors funding them, and researchers pushing the boundaries of what's possible. The format was intimate—"living room conversations" rather than formal panels—which created space for the kind of candid, unfiltered dialogue that's increasingly rare in our industry.

Before diving into what I learned, I want to thank the incredible group of people who made this conversation so valuable:

- Kartik Tiwari (Co-founder & CTO, Andromeda Surgical)

- Hans Peter Brøndmo (Former VP, Google X)

- Animesh Garg (CEO/Assistant Professor, Nouxel AI/Georgia Tech)

- Fady Saad (Founder & General Partner, Cybernetix Ventures)

- Ignacio Galiana (Co-founder & CEO, Verve Motion)

- Jennifer Roberts (Co-founder & Managing Partner, Grit Ventures)

- Mike Xia (Co-founder & CEO, Anvil Robotics)

What follows is my synthesis of the key insights from our discussions. In keeping with the Chatham House Rule, I'm sharing the ideas and learnings without attributing specific comments to specific individuals. The goal is to capture the collective wisdom that emerged from these conversations in a way that's useful for other founders and investors navigating this complex landscape.

Part I: Robotics as an Investment Class—Finally Coming of Age

The Evolution from "Hardware is Hard" to "Hardware is Happening"

For as long as I've been in this industry, robotics has occupied an awkward position in the venture capital world. It's not quite SaaS, with its predictable metrics and rapid scaling. It's not quite biotech, with its clear regulatory milestones and binary outcomes. It's been this in-between category that makes investors nervous—long development cycles, capital-intensive manufacturing, complex supply chains, and uncertain paths to profitability.

But something fundamental is shifting. The conventional wisdom from just five years ago—that hardware is hard, margins are low, and it takes a decade to see returns—is being challenged by a new generation of robotics companies. Development timelines that used to be measured in years are now measured in months. Hardware margins that were once anemic are starting to look surprisingly similar to software margins. And the integration of AI into physical systems is creating ongoing value that extends far beyond the initial hardware sale.

This transformation hasn't gone unnoticed. Multiple participants noted that traditional SaaS investors are now actively building robotics portfolios. One investor shared that their robotics investments had grown from three or four companies to over a dozen in just the past year. This isn't just opportunistic diversification; it reflects a genuine conviction that AI-enabled robotics represents a massive opportunity.

However, the conversation was quick to emphasize that this doesn't mean robotics is just "SaaS with hardware." The risks are different, and in many ways more severe. A bug in a SaaS product can be patched with a software update. A fundamental flaw in a robot's mechanical design, reliability, or safety systems can be catastrophic—both for the customer and for the company. This demands a different approach to due diligence, a different kind of founder expertise, and a different framework for evaluation.

The Business Model Revolution: Beyond the RaaS Hype

Around 2015, Robotics-as-a-Service (RaaS) emerged as the hot new model. The pitch was compelling: instead of asking customers to make large capital expenditures on unfamiliar technology, robotics companies would deploy their systems and charge for usage, retaining ownership and control. This would lower the barrier to adoption, create predictable recurring revenue, and align incentives between vendor and customer. It seemed like the perfect marriage of SaaS economics and robotics deployment.

The reality, as our conversation made clear, has been far more nuanced. There is no one-size-fits-all business model in robotics. Customer preferences vary dramatically across industries, company sizes, and even individual procurement departments. Some customers want to buy equipment outright for depreciation purposes. Others prefer subscription models. Still others want hybrid arrangements with upfront fees and ongoing service charges.

The key insight that emerged was this: flexibility on business model structure, but rigor on unit economics. Investors and founders alike emphasized that the specific revenue model matters far less than the fundamental economics of each deployment. The critical questions are: What does it cost to deploy this system? What revenue does it generate over its lifetime? What is the contribution margin? Is there a clear path to profitability at scale?

One founder described an approach of obsessive contribution margin analysis for every single deployment decision. Before signing a customer, before entering a new vertical, before setting pricing, they run the numbers to ensure that the economics work. This discipline has allowed them to be flexible on deal structure while maintaining a sustainable business model.

This approach also recognizes a fundamental difference between robotics and SaaS: stickiness. The analogy that resonated with me was about fitness apps versus exercise equipment. You might try five different running apps in a year, switching based on features, price, or just boredom. But you only buy one Peloton. The decision takes longer, involves more stakeholders, and requires a bigger commitment. But once that bike is in your home, you're using it for years. The switching costs are enormous.

This stickiness creates opportunities that don't exist in pure software. Once a robot is integrated into a customer's operations, trained into their workforce, and embedded in their processes, removing it is incredibly disruptive. This creates a foundation for multiple revenue streams: the initial sale or lease, installation and integration services, ongoing maintenance and support, software upgrades, data analytics, and training. The most successful robotics companies are those that think creatively about how to structure these revenue streams in ways that create value for customers while building a sustainable business.

The ROI Imperative: Months, Not Years

If there was one point on which every single person in the room agreed without reservation, it was this: customer ROI must be measured in months, not years.

The specific targets varied slightly—some said four to six months, others argued it needed to be even faster—but the principle was universal. A robotics solution that takes two or three years to pay for itself is a non-starter in today's market. The payback period needs to be so short that it's almost a no-brainer for the customer.

This requirement fundamentally reshapes how founders need to think about product development and go-to-market strategy. It forces an intense focus on high-value applications where the impact is immediate and quantifiable. It's no longer sufficient to have impressive technology or to solve an interesting problem. You need to be able to walk into a customer's facility and demonstrate, with data and specificity, exactly how your robot will save them money or generate revenue, and how quickly those benefits will materialize.

This also makes utilization a critical metric. A robot that performs a single task for an hour a day, no matter how well it performs that task, is going to struggle to deliver the ROI that customers demand. The most successful products are those that can be utilized across multiple tasks, for extended periods, maximizing the value extracted from the hardware investment. This is why flexibility and configurability are so important—not for their own sake, but because they directly impact utilization and therefore ROI.

The conversation also touched on the risks of trying to accelerate adoption through free pilots or heavily discounted initial deployments. While this approach can work in SaaS, where marginal costs are low, it can be counterproductive in robotics. Without meaningful financial commitment from the customer, you may not get engagement from the right stakeholders, you may not get the operational changes necessary for success, and you may end up with a deployment that fails not because of the technology but because of insufficient customer buy-in. Setting a meaningful minimum engagement threshold, even if it slows initial growth, can actually accelerate long-term success by ensuring that deployments are set up to succeed.

Supply Chain: From Cost Center to Strategic Weapon

One of the most eye-opening parts of the conversation was the discussion of supply chains, particularly the ecosystem in Asia. The reality is that virtually every robotics company has some dependence on Chinese, Taiwanese, or Korean suppliers. Components from China are often dramatically cheaper and smaller—one person described seeing gears that were a tenth the cost and a tenth the size of Western alternatives. This creates a practical dependency that's difficult to eliminate entirely, even for companies actively pursuing multi-sourcing strategies.

But the conversation went much deeper than just cost. What emerged was a picture of the Asian supply chain ecosystem as a potential source of strategic advantage, not just a cost center to be managed. The example that stuck with me was about DJI, the drone company. By working closely with Taiwanese partners to design custom system-on-chip solutions and convincing TSMC to fabricate them, DJI achieved a six-fold increase in margins while simultaneously doubling battery life and reducing system complexity. This wasn't just about finding cheaper components; it was about strategic partnership with suppliers who could drive fundamental innovation in the product.

This level of engagement with the supply chain is something that many Western robotics companies haven't fully embraced. There's a tendency to view suppliers as vendors to be managed at arm's length, rather than as potential partners who can contribute to product innovation. The companies that figure out how to tap into the deep expertise in hardware design and optimization that exists in Asia—while also building resilience through multi-sourcing and simplification—will have a significant competitive advantage.

The conversation also touched on the unique characteristics of the Chinese market, which was described as a "land of no SaaS." Chinese consumers generally don't pay for software subscriptions, which means that companies like Roborock, which sells robot vacuums with sophisticated software features, generate zero recurring revenue. All revenue comes from hardware sales. This has created an ecosystem that's optimized for rapid hardware iteration, cost reduction, and new product development in a way that's fundamentally different from Western markets. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for any company competing globally.

What Investors Are Really Looking For

The discussion of investor expectations revealed a set of evaluation criteria that are specific to robotics and often quite different from what matters in SaaS. Here's what emerged as the key factors:

Unit Economics and Contribution Margin: Rather than obsessing over recurring revenue percentages or other SaaS-specific metrics, investors want to understand the fundamental economics of each customer deployment. What does it cost to manufacture, deploy, and support? What revenue does it generate over the customer lifetime? What is the contribution margin, and how does it improve with scale? Companies that can demonstrate strong unit economics with a clear path to profitability are far more attractive than those chasing growth metrics borrowed from SaaS playbooks.

Customer ROI and Utilization: As discussed above, customer ROI is paramount. Investors want to see evidence that customers are achieving rapid payback, and they want to understand utilization rates across different use cases. High utilization indicates both strong product-market fit and the potential for customers to expand their deployments.

Supply Chain Strategy: Investors are increasingly sophisticated about supply chain risks and opportunities. They want to understand dependencies on specific suppliers or geographies, strategies for multi-sourcing and risk mitigation, and whether the company is engaging strategically with suppliers to drive innovation or simply managing them as a cost center.

Stickiness and Expansion: Given the longer sales cycles in hardware, customer retention and expansion are crucial. Once a robot is deployed, how likely is the customer to expand to additional units or locations? What are the switching costs? What is the strategy for growing within existing accounts?

Path to Profitability: While growth is important, the path to profitability is paramount. Robotics companies can't rely on the "growth at all costs" playbook that worked for some SaaS companies in the zero-interest-rate era. Sustainable unit economics from early deployments are essential, and investors want to see a clear plan for how the company will reach profitability as it scales.

The Complexity of Go-to-Market

Another theme that emerged was the complexity of go-to-market in robotics, particularly the role of integrators, distributors, and service providers. Unlike SaaS, where companies often sell directly to end users through inside sales or product-led growth, robotics companies frequently navigate a complex ecosystem of intermediaries.

The example that illustrated this best was a company doing ship hull cleaning and inspection. The ultimate customers are major shipping companies, but those companies have long since outsourced such work to specialized service providers. So the question becomes: Do you sell to the service providers? Do you partner with them? Do you try to bypass them and sell directly to the shipping companies? Each approach has different implications for margins, customer relationships, and speed to market.

Another example was a company that developed an autonomous tractor, licensed the technology to Bobcat, and now offers farming-as-a-service. In this model, the robotics company owns the customer relationship and captures ongoing service revenue, while Bobcat handles manufacturing and distribution through its extensive dealer network. This recognizes the reality that in many industries, dealers and distributors have decades-old customer relationships that are nearly impossible for a new entrant to replicate.

The key takeaway was the importance of understanding the structure and maturity of the value chain in any target vertical. In some industries, the ecosystem of integrators and service providers is well-developed and can accelerate go-to-market. In others, the lack of such infrastructure means that the robotics company must build the entire go-to-market capability itself, which can be prohibitively expensive and slow. This should be a key factor in vertical selection and go-to-market strategy.

Data as the New Moat

A theme that came up repeatedly was the strategic importance of data. Robotics deployments generate massive amounts of data about operations, performance, environmental conditions, and usage patterns. This data can be used to continuously improve the product, provide insights to customers, and create new service offerings.

One founder described how their product today is fundamentally different from what it was a year ago, not because of hardware changes, but because of the intelligence and insights derived from accumulated data across all their deployments. The robot learns from every interaction, every environment, every edge case. This continuous improvement creates a natural justification for recurring revenue relationships—customers expect that the equipment they deploy will get smarter over time, with regular software updates, new capabilities, and operational insights.

This expectation, which has been shaped by consumer experiences with smartphones and other connected devices, creates an opening for robotics companies to build subscription models on top of hardware sales. The key is ensuring that the ongoing value is real and tangible, not just a way to extract more revenue from customers.

Looking forward, several participants saw potential for data monetization as an additional revenue stream. While the current focus is on using data to improve products and help customers scale their deployments, future opportunities might include tiered data access (basic versus enterprise), advanced analytics tools, or industry benchmarking services. However, the immediate priority is using data to deliver core product value, with monetization as a longer-term opportunity once the primary value proposition is firmly established.

Part II: The Foundation Models Debate—Tempering Expectations

The second major theme of our conversation was robotics foundation models—the idea that we might be on the verge of a "ChatGPT moment" for physical AI. This topic generated the most debate and revealed the widest range of perspectives.

What Do We Even Mean by "Foundation Model"?

The conversation began with an acknowledgment that the term "foundation model" in robotics is something of a Rorschach test. Different people see different things in it, shaped by their backgrounds, their companies, and their hopes for the future.

From a technical perspective, the core concept is about learning shared principles that apply across multiple tasks, environments, and even robot platforms. Rather than training a separate model from scratch for each specific application, the idea is to learn fundamental concepts of motion, perception, and reasoning that can be adapted or fine-tuned for particular use cases. This approach promises to compound value across products—each new application builds on a shared foundation rather than starting from zero.

However, even this definition encompasses a wide spectrum of ambition. At the narrow end is something like a bimanual manipulator that can reliably pick up and manipulate objects on a table across a range of lighting conditions, object materials, and environmental variations. This is an end-to-end model that takes sensory input and directly outputs motor commands, demonstrating generalizable, robust, multi-task capability. This is the kind of thing that companies like Physical Intelligence are working toward, and it's within the range of current research and beginning to enter reality.

At the ambitious end is something like "go clean the bathroom"—a robot that can understand a vague, high-level natural language command, reason about what it means in context, plan a sequence of actions, navigate to the appropriate location, and execute a complex, multi-step task in an unstructured environment. This is the vision that captures imaginations and drives investment pitches.

The consensus in the room was clear: the narrow end is achievable in the near term; the ambitious end is decades away. And comparisons to ChatGPT, while tempting, are fundamentally misleading when applied to the ambitious end of the spectrum.

Why Robotics Isn't Having Its "ChatGPT Moment" Anytime Soon

The skepticism about an imminent breakthrough in general-purpose robotics was palpable and well-reasoned. It rests on several fundamental differences between language AI and physical AI.

First, robotics is a much more complex, multi-dimensional problem than language. Language models operate entirely in the digital realm, processing text and generating text. The physical world introduces challenges of perception, manipulation, navigation, and interaction that have no analogue in language processing. The state space is vastly larger, the consequences of errors are more severe, and the requirements for reliability are far more stringent.

Second, the success of language models was built on the availability of massive training datasets. Essentially the entire internet's worth of text was available for training. For robotics, no such dataset exists. There is no vast library of physical interactions, manipulation demonstrations, or tactile experiences that can be scraped and used for training. Creating such a dataset would require deploying thousands of robots in diverse environments for extended periods, carefully logging every interaction—a task that is orders of magnitude more difficult and expensive than scraping web pages.

Third, the nature of the problems is fundamentally different. Language models can be "good enough" while still making errors. A poorly written poem or an inaccurate summary is a minor inconvenience. Physical robots, especially in applications like surgery, manufacturing, or logistics, must be predictable and reliable. As one person memorably put it, "Building a really good product requires predictability. You have to solve the problem, but you also have to solve the problem predictably. Especially if you're holding a knife."

This requirement for predictability and reliability means that the bar for success in robotics is much higher than in language models. It's not enough for a robot to usually pick up a cup correctly; it needs to do so reliably, every time, across a wide range of conditions. This is a fundamentally harder problem than generating plausible-sounding text.

Sense, Plan, Act: Where's the Bottleneck?

To make the discussion more concrete, we used the classic robotics framework of Sense-Plan-Act to assess the current state of the art and identify where the real challenges lie.

Sensing is largely considered a solved problem. Modern computer vision systems can identify objects, estimate poses, understand scenes, and handle varying lighting conditions with remarkable accuracy. The integration of vision with other sensory modalities, including speech, has advanced rapidly. While challenges remain, particularly in tactile sensing and fine-grained manipulation feedback, the sensing component is no longer the primary barrier to progress.

Planning is advancing rapidly and was described as "surprisingly very close" to being capable of sophisticated high-level task decomposition. Modern AI systems, particularly large language models with vision capabilities, can look at a scene, understand a goal, and generate a reasonable plan of action. If you show a system a picture of a kitchen and ask "how would I make eggs, undercooked," it can generate a step-by-step plan. The procedural knowledge and common sense reasoning required for planning are increasingly present in AI systems.

Acting is where the fundamental bottleneck lies. This is where, as one person put it, "the rubber meets the road." The problem is that planning systems output programs or sequences of high-level actions—"break eggs," "flip omelet," "plate food"—but these are subroutines that current robotic systems cannot reliably execute. The gap between a symbolic plan and the low-level motor control required to execute it in the physical world remains vast.

This execution gap is not "just manipulation," as was emphasized in the conversation. It is the core challenge of physical AI. The more robust subroutines a system has—the more basic physical skills it can reliably perform—the richer the language of possible actions becomes. But building this repertoire of reliable, generalizable physical skills is proving to be extraordinarily difficult. It requires not just learning from data, but learning to interact with the physical world in all its messy, unpredictable complexity.

The Fundamental Data Challenge

The lack of training data for physical AI came up repeatedly as a critical barrier. One person posed the challenge directly: "The reason that we could build ChatGPT and Claude and DALL-E and all these things is there's an enormous amount of imagery and audio and text available in digital form. There's nothing like that anywhere close for touch. How do we build general-purpose robotics foundation models without that?"

Current approaches include synthetic data generation through simulation and teleoperation, where humans control robots to demonstrate tasks. However, these are considered partial solutions at best. Simulation has its own challenges, including the "sim-to-real gap"—the difference between how things behave in simulation versus the real world. Simulations that are close to reality but not quite right can actually be worse than simpler models, creating what was described as an "uncanny valley" problem.

Teleoperation is expensive and slow, and the data it generates may not capture the full range of variation needed for robust generalization. Moreover, there's a question of whether we're even collecting the right kind of data. Perhaps what's needed isn't billions of examples of every possible interaction, but rather data that helps specify reward functions for reinforcement learning. The idea is that robots can learn through self-supervised interaction with the environment, but they need data to understand what constitutes success.

This is a fundamentally different data collection strategy than the broad scraping approach used for language models. It's more targeted and purposive, but it also requires a much deeper understanding of what the robot needs to learn and how to structure the learning process. This is an active area of research, but it's far from solved.

Simulation: Promise and Peril

The role of simulation in addressing the data challenge generated interesting discussion. On one hand, simulation has made remarkable progress in recent years, particularly in content generation for simulated environments. For navigation tasks, simulation is already largely sufficient. For autonomous driving, simulation is used in the loop to test edge cases and rare scenarios that would be dangerous or impractical to encounter in the real world.

However, for manipulation and contact-rich tasks, simulation remains a significant challenge. The issue isn't primarily about physics—as was pointed out, model-based control has shown for decades that models don't need to be perfectly accurate to be useful for control. The real challenge is content generation. Who creates the detailed, realistic simulated environments in which robots can train? This is a labor-intensive process, and while AI is beginning to help automate it, we're still far from being able to generate arbitrary realistic environments on demand.

There's also the risk of model collapse when training on synthetic data. If you train a model on data generated by another model, and then train another model on that output, you can end up with a degradation of quality over successive generations. This is a known problem in language models trained on internet data that increasingly includes AI-generated content, and it's a potential concern for robotics systems trained primarily in simulation.

The consensus was that simulation is necessary but not sufficient. We need both simulation for safe, scalable training and real-world interaction for grounding and validation. The companies that figure out how to effectively combine sim and real, using each for what it's best at, will have a significant advantage.

Platform vs. Product: A Crucial Strategic Choice

One of the most thought-provoking parts of the conversation was the tension between building a general-purpose platform versus building a specific, valuable product. The platform vision is compelling: robots as a new container for computing, like the PC or the smartphone, with AI as the middleware that enables a rich ecosystem of applications. In this view, we're building the infrastructure for a new computing paradigm.

However, the counterargument was equally compelling, drawn from hard-won experience at major tech companies: "You earn the right to build a platform. First you build a product. And if that product is really successful, you earn it." The danger of thinking platform-first is that you end up building something technically impressive but commercially unviable—a system that doesn't solve any specific customer problem well enough to gain traction.

The more pragmatic path, and the one that seemed to resonate most in the room, is to focus on building robots that deliver tangible value on specific tasks. These robots will be multi-purpose and configurable, but they will be designed and sold as products, not as open-ended platforms. They will have clear use cases, clear value propositions, and clear paths to ROI. Over time, as these products succeed and a common set of capabilities emerges, a true platform may begin to take shape. But that's a consequence of product success, not a starting point.

This approach also addresses a practical challenge: the lack of standards in robotics. Currently, robotics systems are vertically integrated, with tight coupling between hardware and software. This integration is necessary given the current state of the technology, but it limits the ability to create a true platform ecosystem. One company described their efforts to create a common interface layer—"a version of CUDA for robotics"—that would allow developers to build applications without worrying about low-level details like time synchronization, latency, and control loops. Such standards, if they emerge and gain adoption, could enable the kind of platform ecosystem that many envision. But that future remains uncertain, and the immediate focus must be on products that work.

Form Factor: Function Over Fashion

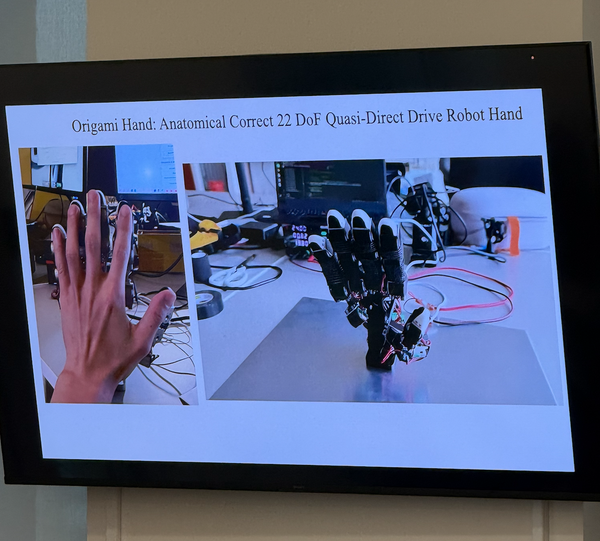

No discussion of modern robotics would be complete without addressing form factors, particularly the recent wave of enthusiasm for humanoid robots. The conversation here was refreshingly pragmatic, grounded in a fundamental engineering principle: form should follow function.

The humanoid form factor has undeniably done wonders for bringing mainstream attention to robotics. For the first time in history, robotics is a topic of mainstream conversation, driven in large part by high-profile humanoid projects. And for certain applications—particularly those involving environments designed for humans, such as space stations or existing factories—the humanoid form factor may indeed be optimal.

However, the conversation pushed back against the assumption that humanoid is the default or inevitable form factor for most robotics applications. The point was made that much of the serious investment in humanoid robotics is motivated by a specific long-term goal: space exploration and colonization. In that context, humanoid makes sense because the environments and tools are designed for human bodies. But for terrestrial applications, the case is far less clear.

The analogy that stuck with me was: "When we invented flying machines, we didn't make them flap their wings." Nature's solutions are often not the most efficient engineering solutions. For many robotics applications, specialized form factors—wheeled, tracked, snake-like, or something entirely novel—will be more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective than humanoid designs.

The key is to start with the customer problem, understand the requirements and constraints, and design the optimal form factor for that specific application. Sometimes that might be humanoid, but often it won't be. One person noted, "You don't put a humanoid in the water as a diver to clean a ship hull. You have something that adheres magnetically to the ship hull. Or sometimes you need a snake or a bird."

The economics and energy efficiency of different form factors also matter significantly. Humanoid robots are complex, expensive, and energy-intensive. For many applications, simpler form factors can deliver the same or better functionality at lower cost and with greater reliability. The companies that succeed will be those that resist the temptation to chase the humanoid trend and instead focus relentlessly on the optimal solution for their specific use case.

Synthesis: What This Means for Founders and Investors

For Founders: A Pragmatic Roadmap

Coming out of these conversations, several clear implications emerged for robotics founders:

Obsess over customer ROI. This cannot be overstated. Your product must deliver measurable value in months, not years. This should shape every product decision, every feature prioritization, and every go-to-market choice. If you can't articulate a clear, compelling ROI story, you don't have a product-market fit yet.

Be flexible on business models, but rigorous on unit economics. Don't force a particular revenue model on your customers. Understand what they want and how they prefer to buy. But regardless of the structure, ensure that every deployment has positive contribution margins and a clear path to profitability. Run the numbers obsessively.

Engage strategically with your supply chain. Your suppliers are not just vendors; they're potential partners who can drive innovation in your product. This is particularly true in Asia, where there's deep expertise in hardware design and optimization. Build relationships, share your roadmap, and look for opportunities to co-develop solutions. At the same time, build resilience through multi-sourcing and simplification.

Map the entire value chain. Understand the ecosystem of integrators, distributors, and service providers in your target vertical. Decide early whether you'll partner with them, sell through them, or attempt to bypass them. This decision will have profound implications for your go-to-market speed, margins, and customer relationships.

Design for data from day one. Your robots should be generating valuable data from the moment they're deployed. Use that data to continuously improve performance, provide insights to customers, and build switching costs. This creates a natural justification for recurring revenue and a moat against competition.

Build products, not platforms. Resist the temptation to build a general-purpose platform before you've proven product-market fit. Focus on solving specific customer problems exceptionally well. If you succeed, a platform may emerge naturally. If you fail, at least you'll have learned something concrete about customer needs.

Let form follow function. Design your robot's form factor based on the problem you're solving, not on assumptions about what a robot "should" look like. Be willing to embrace unconventional designs if they offer better performance, reliability, or economics. The humanoid hype will fade; good engineering endures.

Be realistic about AI capabilities. Current AI is powerful for sensing and planning but remains limited in its ability to execute reliable physical actions. Design your product around what AI can do today, not what you hope it will do tomorrow. Focus on building robust subroutines and creating a repertoire of reliable skills that can be composed into more complex behaviors.

For Investors: A New Evaluation Framework

For investors, these conversations highlighted the need for a robotics-specific evaluation framework:

Develop domain expertise. Robotics companies cannot be evaluated using pure SaaS metrics. Invest in understanding the unique characteristics of hardware development, including manufacturing, supply chain, integration, and deployment. Build relationships with technical advisors who can help you assess the engineering risk.

Focus on unit economics. Dig deep into the economics of each customer deployment. What does it cost to manufacture, deploy, and support? What revenue does it generate over the customer lifetime? What is the contribution margin? Is there a clear path to profitability at scale? These questions matter more than growth rate or recurring revenue percentage.

Assess customer ROI rigorously. Companies that can't deliver customer ROI in months will struggle to scale. Ask about utilization rates, flexibility across use cases, and the specific value proposition. Be skeptical of long payback periods or vague value claims. The best companies can articulate their ROI story with precision and data.

Evaluate supply chain as strategy. The supply chain is both a risk and an opportunity. Understand the company's dependencies, multi-sourcing strategies, and relationships with key suppliers. Look for companies that are engaging strategically with the supply chain to drive innovation, not just managing it as a cost center.

Understand go-to-market complexity. Map the value chain in the target vertical. Is there an established ecosystem of integrators and distributors, or will the company need to build go-to-market capabilities from scratch? How does the company plan to own the customer relationship? What are the implications for margins and scaling speed?

Look for data-driven moats. Companies that are generating valuable data and using it to improve products and provide customer insights have a natural path to recurring revenue and customer lock-in. Evaluate the data strategy as a core component of the business model, not an afterthought.

Be patient on foundation models, opportunistic on applications. The path to general-purpose robotics foundation models is long and uncertain. While it's worth tracking research progress, near-term investment opportunities are more likely to be in companies applying today's AI to specific, high-value applications. Look for companies that are pragmatic about current capabilities and focused on delivering value today.

Assess technical risk realistically. Robotics involves both software and hardware risk, and mistakes in hardware are more costly than in software. Evaluate the team's engineering capabilities, their approach to reliability and testing, and their track record of execution. Be particularly cautious about companies making bold claims about AI capabilities that exceed the current state of the art.

Final Thoughts: The Long Game

What struck me most about these conversations was the sense of pragmatic ambition that pervaded the room. The wild, blue-sky thinking of a few years ago—when every robotics pitch seemed to promise general-purpose humanoid assistants within five years—is being replaced by a more grounded, business-focused approach. The industry is maturing, and the focus is shifting from what is technically possible to what is commercially viable.

This is a healthy and necessary evolution. The challenges in physical AI are immense, but the opportunities are even greater. The physical world is vastly larger and more complex than the digital realm, and we are still in the very early stages of understanding how to build intelligent systems that can operate within it.

The companies that succeed in this new era will be those that combine a bold, long-term vision with a relentless, near-term focus on delivering value to customers. They will solve real-world problems, build sustainable businesses, and, step by step, create the foundation for the intelligent, robotic future we all envision. They will understand that the path to general-purpose AI for robotics, if it exists, runs through thousands of specific, valuable applications, each teaching us something new about how to interact with the physical world.

For founders, this means resisting the siren call of platform thinking and focusing on building products that customers love. It means obsessing over unit economics, customer ROI, and operational excellence. It means being honest about what current technology can and cannot do, and designing products accordingly.

For investors, it means developing new frameworks for evaluation, building domain expertise, and being patient with the unique challenges of hardware development while also demanding clear paths to profitability. It means resisting the temptation to apply SaaS playbooks to a fundamentally different category and instead learning what actually works in robotics.

The future of physical AI will not be built through a single, monolithic breakthrough. It will be built through the steady accumulation of product-driven successes, each solving a real problem, each generating data, each teaching us something new. This is the long game, and it's the only game worth playing.

I'm grateful to everyone who participated in these conversations for their candor, their insights, and their willingness to grapple with hard questions. The robotics industry is better for having these kinds of honest, unfiltered dialogues, and I hope we can continue to create spaces for them.

This post reflects my personal synthesis of the conversations and does not represent the official views of any participant or organization.

Written by Bogdan Cristei and Manus AI