The Dexterity Deadlocks: Why Robots Can Backflip But Can't Fold Laundry - And the CMU PhD Student Fixing It From the Hardware Up

Takeaways from Quanting Xie's presentation at CMU's Lab to Market, San Francisco — February 11, 2026

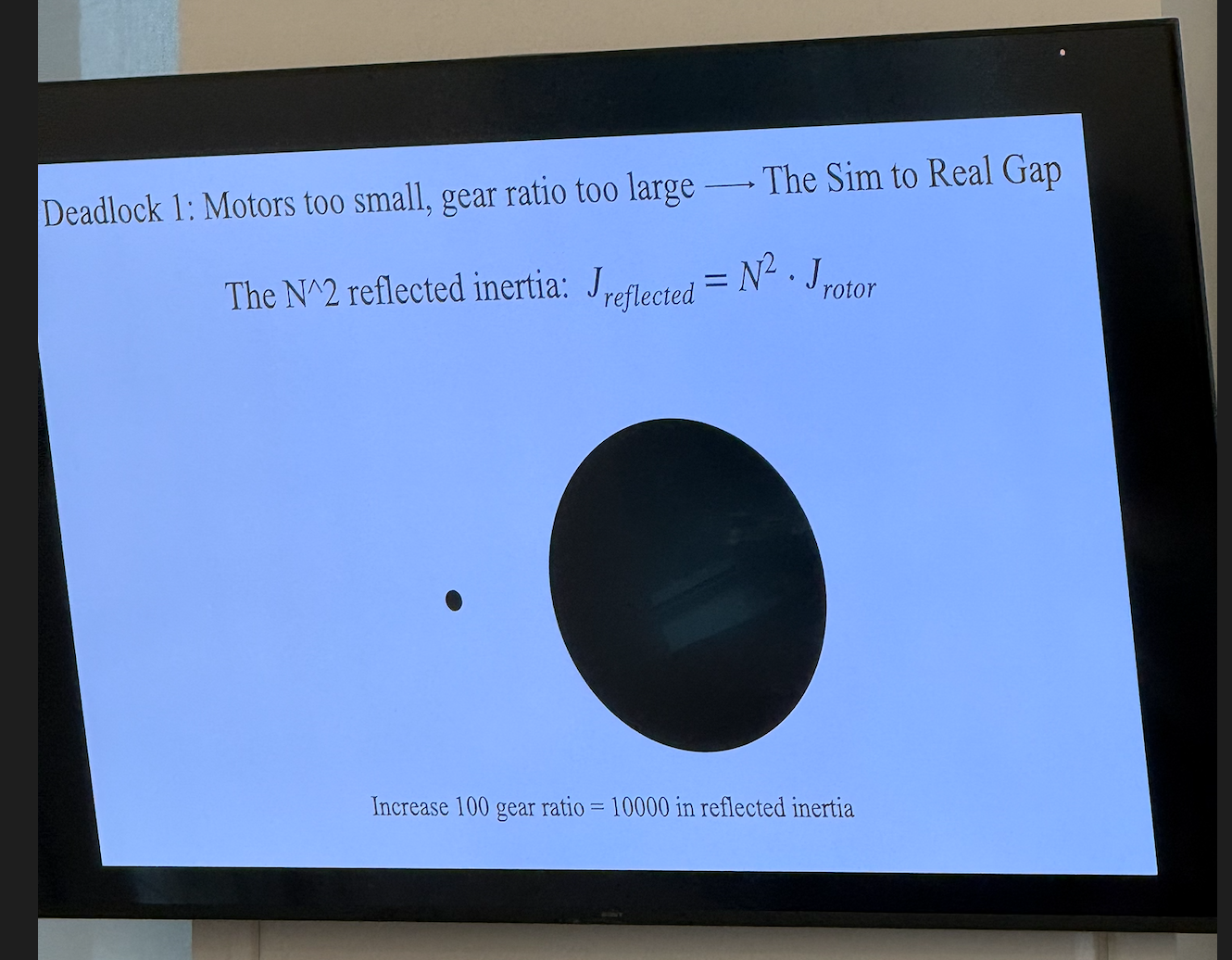

Increase a gear ratio by 100x and the reflected inertia increases by 10,000x.

That single physics problem explains one of the biggest disconnects in robotics right now: we can build robots that walk, run, dance, and do backflips — but we still can't build ones that reliably pick up a coffee mug, thread a needle, or fold a shirt.

Locomotion is largely solved. Dexterous manipulation is not. And the reason might not be what you think.

I spent last week at CMU's Lab to Market event in San Francisco, a full-day program hosted by the Swartz Center for Entrepreneurship that brought together CMU researchers, founders, and investors to explore what's next at the frontier of AI and robotics. Across keynotes, lightning talks, investor panels, and research sessions, the event covered a wide range of topics — from structured numeric reasoning to warehouse autonomy to the question of what's actually fundable in AI right now.

But of everything I heard that day, one presentation stood out. It reframed how I think about the bottleneck in physical AI, and I think it carries real implications for anyone building or investing in the robotics space.

The talk was called "The Dexterity Deadlocks — And How We Broke Them by Fixing the Hardware," delivered by Quanting Xie, a PhD student at CMU's Robotics Institute and co-founder of a startup called Origami Hand.

Here's what he laid out — and why it matters.

The Big Picture: Physical AI Has a Hardware Problem

The dominant narrative in AI right now is that progress is driven by models, data, and compute. Scale up the transformer architecture, collect more demonstrations, throw more GPUs at it, and capabilities will improve. This framing has worked remarkably well for language, vision, and even some aspects of robotics like locomotion.

But Quanting's argument is that for dexterous manipulation — the ability to use hands to interact with objects the way humans do — the bottleneck isn't the model. It's the hardware underneath it. Specifically, the actuators (motors) that power robotic hands are fundamentally inadequate, and no amount of algorithmic cleverness can fully compensate for that.

He framed this as two interlocking "deadlocks" — problems that reinforce each other and have stalled progress in the field for years.

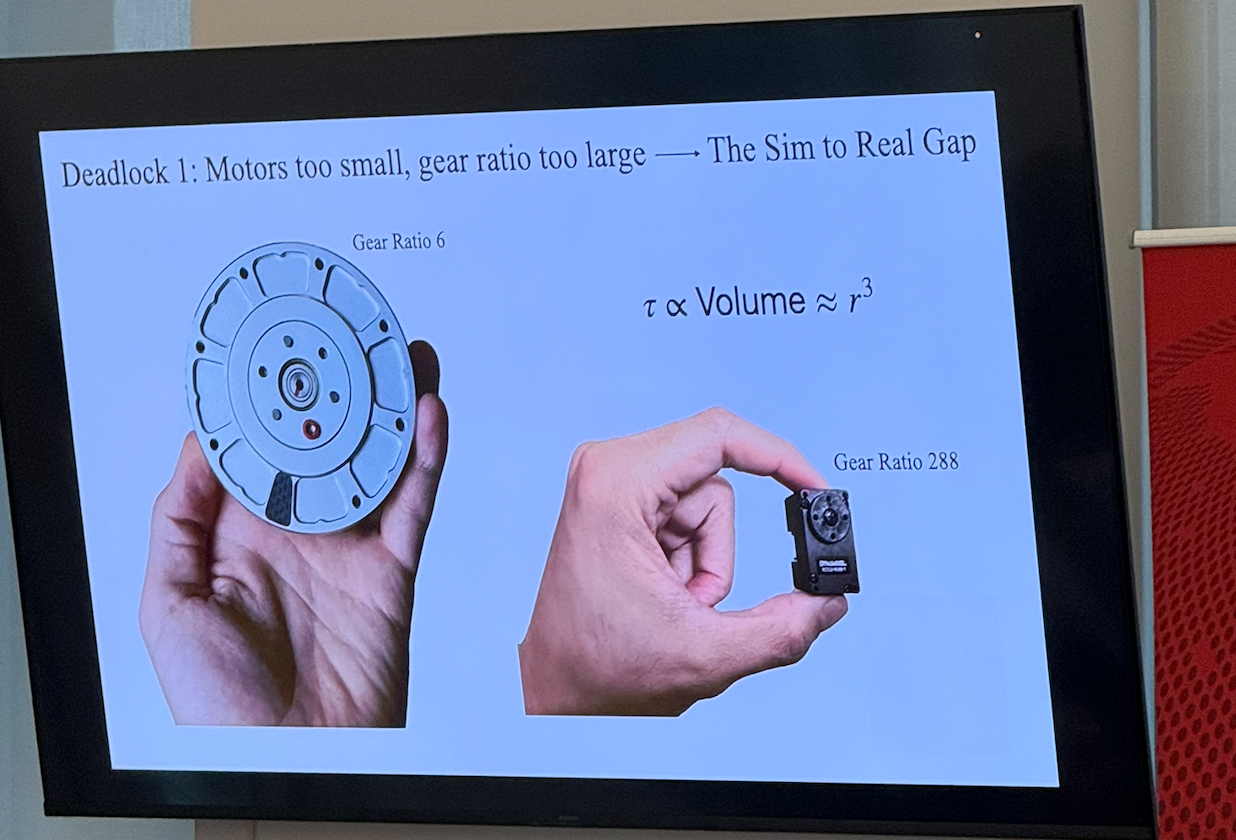

Deadlock 1: Motors Too Small, Gear Ratios Too Large — The Sim-to-Real Gap

If you want a robot hand that's roughly the same size as a human hand, you need small actuators. The problem is that when you shrink a motor, its torque doesn't just decrease proportionally — it decreases cubically with volume. A motor half the size doesn't produce half the torque. It produces roughly one-eighth.

To compensate, engineers use high gear ratios. A small motor with a gear ratio of 288:1 can still produce meaningful torque at the output. Problem solved?

Not even close. High gear ratios introduce three compounding problems that are devastating for learning-based control:

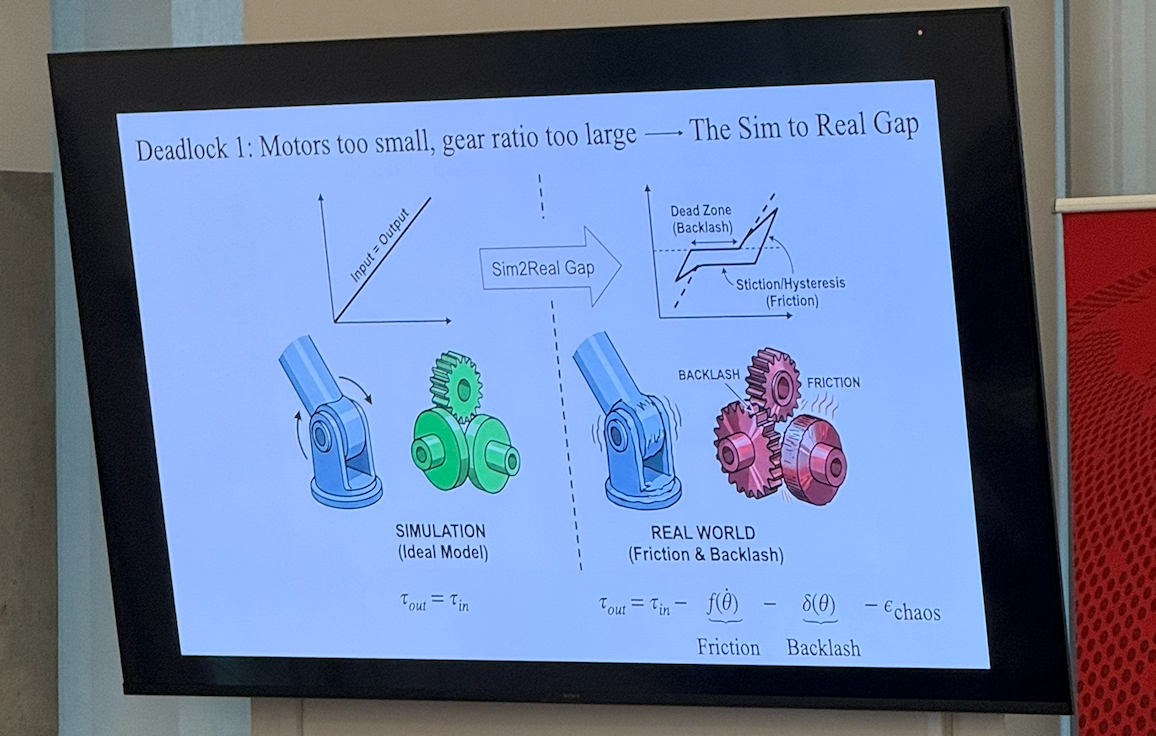

Friction and backlash. Gears aren't perfect. At high ratios, the accumulated friction and mechanical play (backlash) in the gear train become significant. The motor's output becomes noisy, nonlinear, and hard to predict — exactly the opposite of what a learned control policy needs.

The reflected inertia problem. This is the physics insight that anchored the talk. When you put a gearbox on a motor, the inertia that the system "feels" at the output isn't just the rotor inertia — it's the rotor inertia multiplied by the square of the gear ratio. The formula is straightforward:

J_reflected = N² × J_rotor

So if you increase the gear ratio by 100x, the reflected inertia increases by 10,000x. The system becomes incredibly sluggish and resistant to quick changes in motion — which is exactly what dexterous manipulation requires.

The sim-to-real gap. In simulation, physics is clean. Motors are ideal. There's no friction, no backlash, no reflected inertia to worry about. You can train a policy in simulation that works beautifully — and then watch it fail completely on real hardware because all of these effects conspire to make the real system behave nothing like the simulated one.

This is the core of Deadlock 1: small motors force high gear ratios, which destroy the fidelity needed for sim-to-real transfer. And sim-to-real transfer is the primary pathway for scalable robot learning.

Deadlock 2: The Embodiment Gap — Why Robot Hands Can't Learn From Human Hands

The human hand has approximately 22 degrees of freedom — 22 independent axes of motion that give us our extraordinary dexterity. If you want to build a robot hand the same size as a human hand using today's commercial actuators, you face a brutal tradeoff.

With motors this small and weak, you can't put enough of them in a human-sized form factor to match the human hand's degrees of freedom. The result is that most dexterous robot hands are either:

- Human-sized but severely underactuated — something like 6 degrees of freedom instead of 22. They can open and close, but they can't do fine manipulation.

- Fully actuated but far too large — matching human dexterity but at a size that makes them impractical for real-world tasks designed for human hands.

Either way, the robot hand doesn't look like a human hand, doesn't move like a human hand, and doesn't behave like a human hand. This creates what Quanting called the embodiment gap — and it has a direct consequence for data and learning.

One of the most promising approaches in robot learning is learning from human demonstrations. You watch a human perform a task, you map that motion onto the robot, and you use it as training data. But if your robot hand has 6 degrees of freedom and the human hand has 22, the mapping breaks down. The demonstrated motions don't transfer. You end up with strange, unnatural behaviors that fail at the task.

The embodiment gap means you can't efficiently learn from the richest source of manipulation data available: humans.

The Solution: Fix It at the Root — Build Better Actuators

Quanting's thesis is that both deadlocks trace back to the same root cause: actuators that are too weak for their size. If you could dramatically increase the torque density of small motors, you could reduce gear ratios, which would close the sim-to-real gap (solving Deadlock 1) and enable enough actuators in a human-sized hand to close the embodiment gap (solving Deadlock 2).

So that's exactly what his team did.

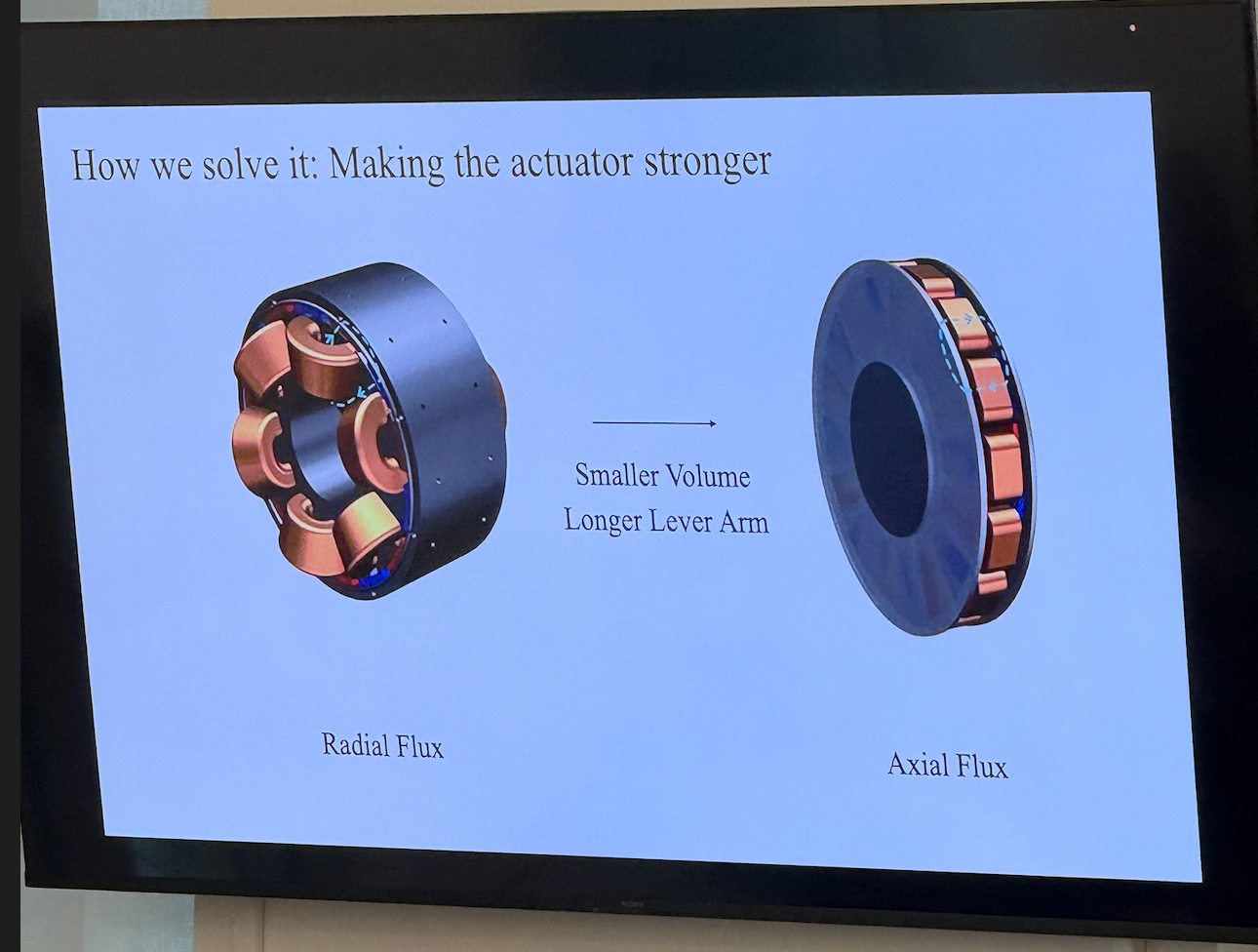

Axial Flux vs. Radial Flux

Traditional electric motors use a radial flux design — the magnetic field runs perpendicular to the axis of rotation, and the rotor spins inside a cylindrical stator. This is the standard architecture used in virtually all small commercial motors.

Quanting's team designed a custom axial flux motor, where the magnetic field runs parallel to the axis of rotation and the rotor is a flat disc. The key advantage: axial flux motors can generate more torque in a smaller volume because of the longer effective lever arm of the magnetic forces. Smaller volume, longer lever arm, more torque per cubic centimeter.

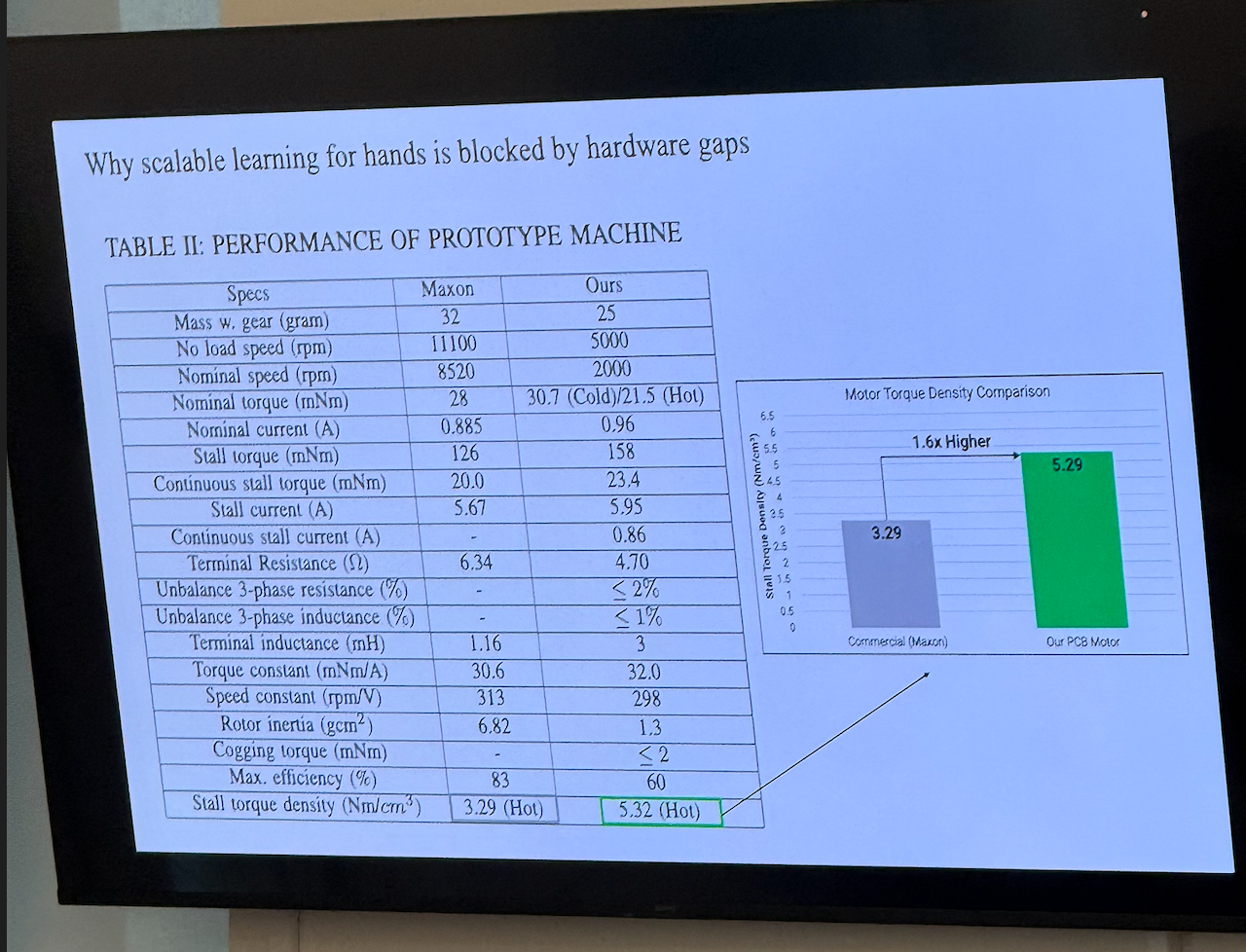

The Results

Their prototype PCB motor achieved a stall torque density of 5.32 Nm/cm³ — compared to 3.29 Nm/cm³ for the best comparable commercial motor (Maxon). That's 1.6x more torque-dense, in a package that's actually lighter (25g vs. 32g).

This matters because it breaks the deadlock chain. With 1.6x the torque density, you can use dramatically lower gear ratios and still get the output torque you need. Lower gear ratios mean less friction, less backlash, less reflected inertia — and a much smaller sim-to-real gap.

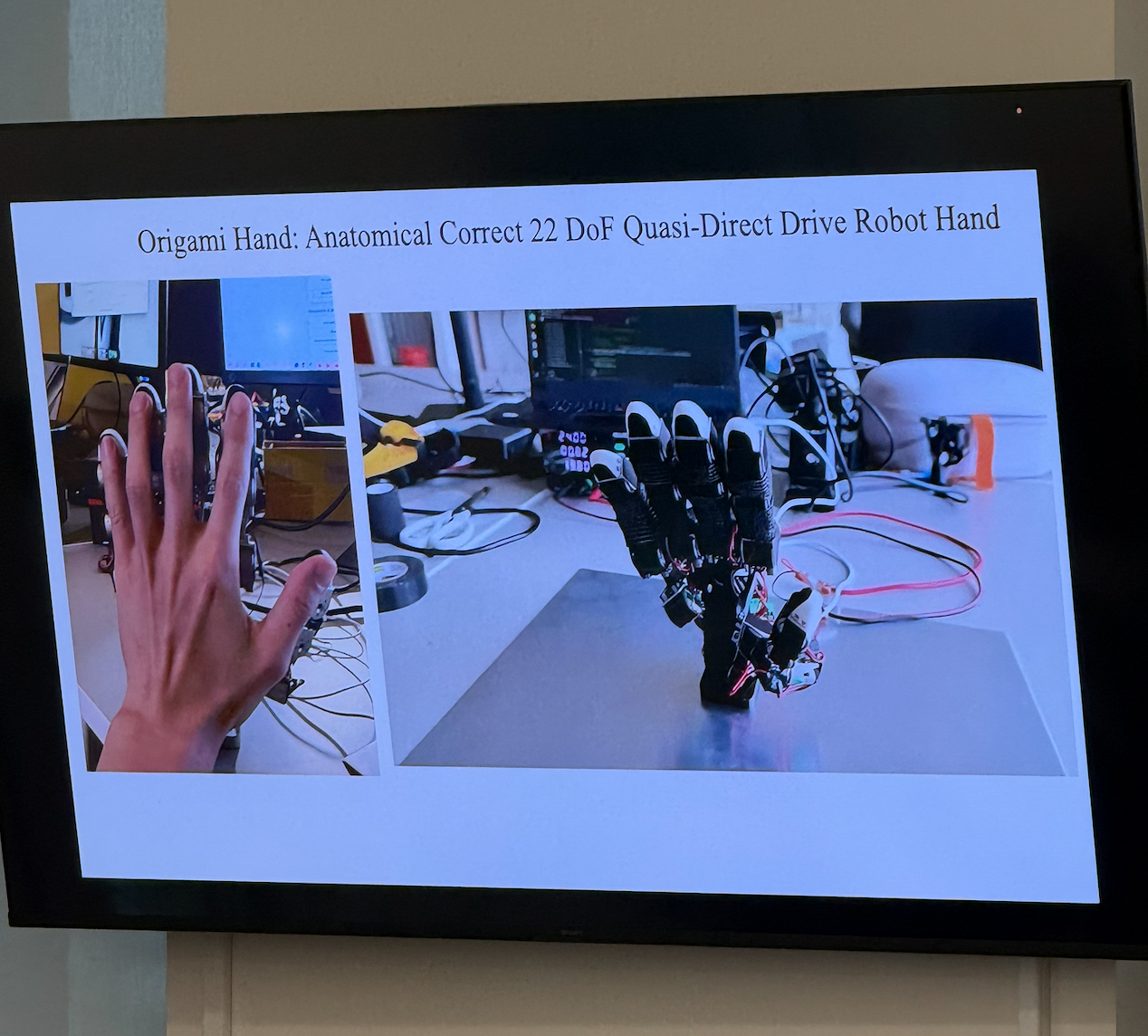

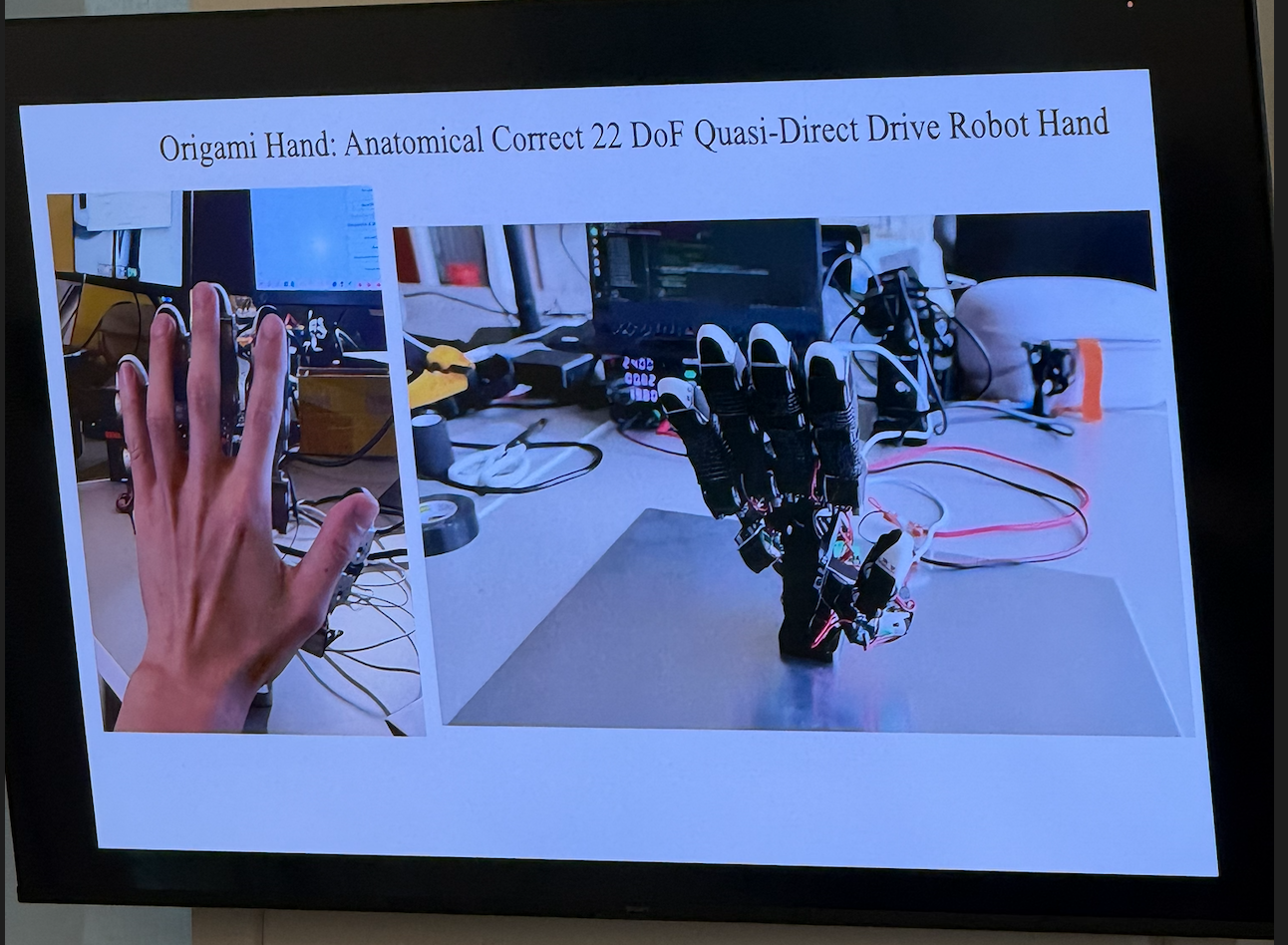

The Origami Hand

With their custom actuators in hand, the team built a complete robotic hand: the Origami Hand. It's a 22 degree-of-freedom, quasi-direct-drive robot hand that is approximately the same size as a human hand.

The design is anatomically informed — Quanting showed how they capture hand data using cameras, analyze joint positions and angles, and then use that data to generate the robot hand's kinematic structure. The goal is a hand where every joint maps directly to a motor (link-motor, link-motor), making it straightforward to simulate and enabling clean sim-to-real transfer.

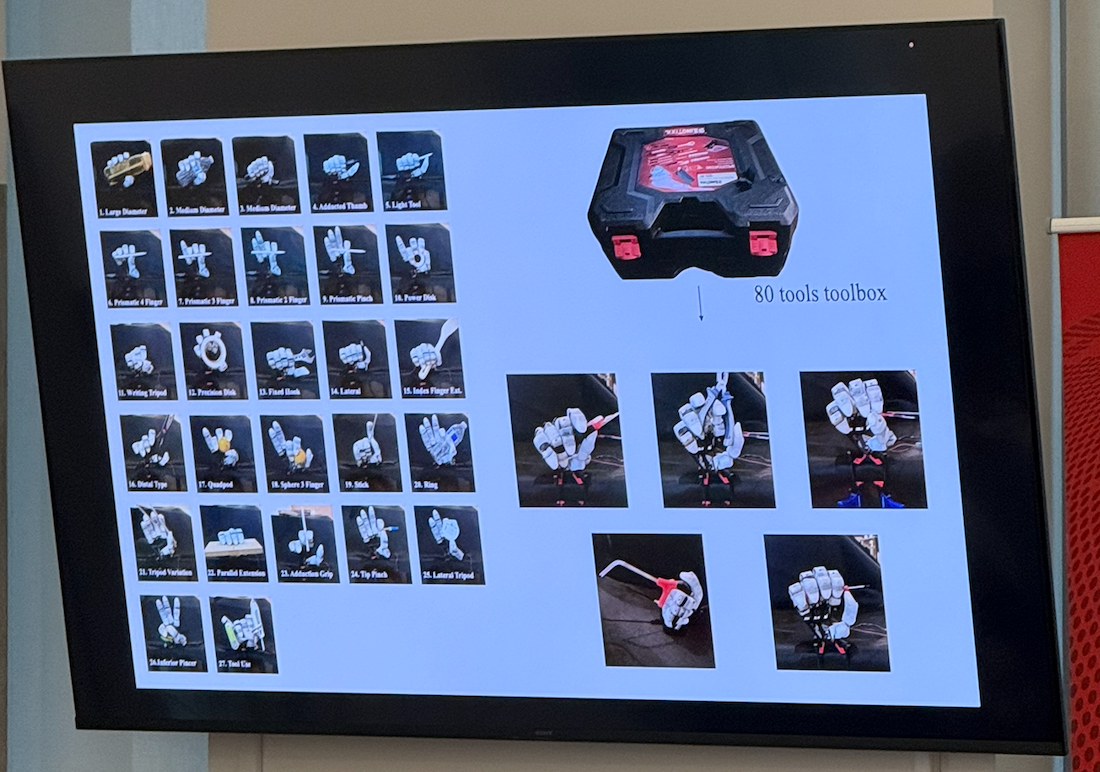

They validated the hand across 27 different grasp taxonomies — the standard classification of human grasp types — and demonstrated it could grasp every tool in an 80-tool toolbox.

Why This Matters for Entrepreneurs and Investors

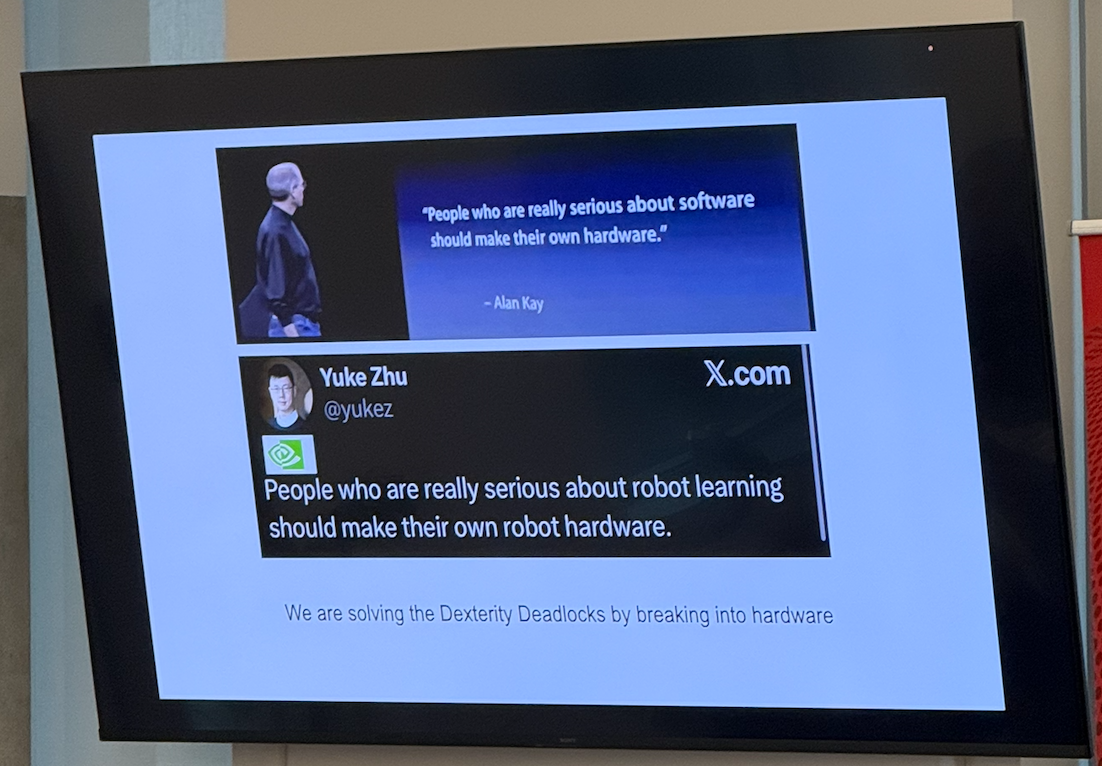

Quanting closed his talk with two quotes that frame the opportunity well. The first from Alan Kay: "People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware." The second, an adaptation by robotics researcher Yuke Zhu: "People who are really serious about robot learning should make their own robot hardware."

There are a few takeaways here that I think are worth sitting with:

The software-only thesis in robotics has limits. The prevailing venture thesis in AI — that software and models are the value layer, and hardware is commoditized — doesn't hold cleanly in dexterous manipulation. When the hardware fundamentally constrains what the software can learn, the hardware becomes the unlock. This is a first-principles insight that's easy to miss if you're pattern-matching from the LLM playbook.

Sim-to-real is a hardware problem, not just a software problem. There's been enormous investment in simulation environments, domain randomization, and transfer learning techniques to bridge the sim-to-real gap. These are all valuable. But Quanting's point is that if your hardware introduces physics that can't be faithfully simulated (high-ratio gearbox friction, backlash, reflected inertia), then no amount of software sophistication will fully close the gap. Better hardware makes every software approach work better.

The embodiment gap is a data problem in disguise. The inability to learn from human demonstrations because your robot doesn't match the human form factor is fundamentally a data access problem. If you can build a hand that closely matches human anatomy and degrees of freedom, you unlock the ability to learn from the largest, cheapest, most diverse source of manipulation data in the world: video of humans doing things.

Hardware moats in robotics may be undervalued. In a market where every robotics company is using the same off-the-shelf actuators and competing on software, a company that builds meaningfully better actuators has a structural advantage. Custom hardware that enables capabilities the competition physically can't achieve is a different kind of moat than a better model or a larger dataset.

The Broader Event: CMU Lab to Market, February 11, 2026

For context, Quanting's talk was part of a much larger day. CMU's Lab to Market event in San Francisco featured a packed lineup:

The morning kicked off with a keynote featuring Sameer Gandhi (Accel) and Aravind Srinivas (Perplexity) on the path from research to category-defining AI companies. This was followed by an investor panel on what's fundable in AI with Jon Chu (Khosla Ventures), Mar Hershenson (Pear VC), Natasha Mascarenhas (Bloomberg News), and Kahini Shah (Obvious Ventures).

A panel on why autonomy is a systems problem featured Arvind Gupta (Mayfield), Martial Hebert (CMU Dean, School of Computer Science), Ryan Oksenhorn (Zipline), Nancy Pollard (CMU Robotics Institute), and Sebastian Scherer (Field AI / CMU Robotics).

The afternoon's lightning talks, emceed by Matt Kirmayer (Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman) with Rocket Drew (The Information), featured three focused conversations: Pradeep Ravikumar (Wood Wide AI) on structured numeric reasoning with Arash Afrakhteh (Pear VC), Brandon Abranovic (Polymath) on AI for CAD and manufacturing with Patrick Chung (Xfund), and Sankalp Arora (Gather AI) on warehouse autonomy with Phil Bronner (Ardent VC).

The research outlook session — where Quanting presented — also included Mosam Dhabi on physical intelligence and the data-scaling bottleneck, Alexandra Ion on human-centered physical AI, Yuyu Lin on personalized rehabilitation devices, and Chenyan Xiong on frontier AI research directions.

The day closed with panels on translating foundational advances to real-world scale (Reeja Jayan, Destenie Nock, Carmel Majidi from CMU Engineering, and Maryanna Saenko from Future Ventures) and a closing keynote on financing the future of robotics with Justin Krauss (JP Morgan), Herman Herman (CMU National Robotics Engineering Center), Kevin Peterson (Bedrock Robotics), and Ruchi Sanghvi (South Park Commons).

It was a dense, high-quality day — and a reminder that some of the most important work in AI is happening not in foundation model labs, but in robotics labs where people are wrestling with atoms, not just bits.

Bottom Line

The dexterity problem in robotics isn't going to be solved by bigger models alone. It requires rethinking the hardware stack from first principles — starting with the actuators. Quanting Xie and the Origami Hand team are doing exactly that, and the early results are compelling: a custom motor that's 1.6x more torque-dense than anything commercially available, a 22-DOF hand that matches human anatomy, and a clear path to closing both the sim-to-real gap and the embodiment gap that have stalled the field.

For entrepreneurs: if you're building in physical AI, pay attention to your hardware assumptions. The actuators you're using may be the ceiling on what your software can achieve.

For investors: the companies that solve hard hardware problems in robotics — not just hard software problems — may end up owning the most defensible positions in the market.

Not just better models. Better atoms.

Slides:

Written by Bogdan Cristei and Manus AI